Why would an original Netflix show have cliffhangers and fades to black at timed intervals as if to accommodate for commercial breaks? In the autumn of 2017, two shows about serial killers were launched on Scandinavian Netflix as original content. Yet only one of them, Mindhunter (2017-2019), was actually made for Netflix while the other one, Manhunt: Unabomber (2017), was picked up by the streaming service after airing on Discovery Channel. The two shows and their differences demonstrate how viewing contexts shape storytelling strategies and that what works well on one platform may actually seem odd on another.

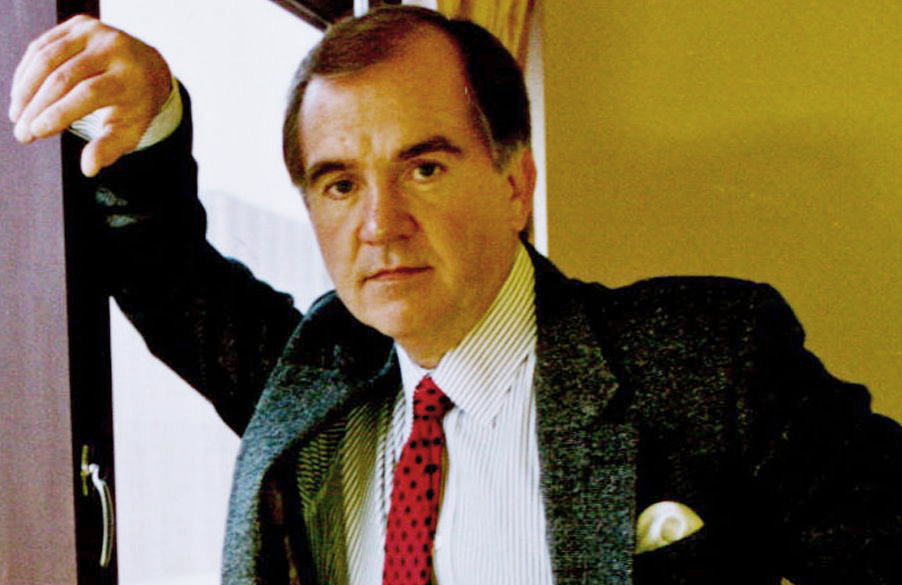

2017 saw the launch of two shows on Netflix about mass murderers, both focusing on criminal psychology and the pioneering attempts of FBI agents to understand the minds of men who kill for unfathomable reasons. In fact, once you start looking, similarities between the two shows seem to abound: Both Mindhunter and Manhunt: Unabomber are period shows, set in the late 70s–early 80s and the mid 90s respectively, and feature famous real-life killers and other actual persons. In both shows, the protagonists face skepticism and even hostility from their peers and superiors, and both shows detail how the main characters, James ‘Fitz’ Fitzgerald (Manhunt: Unabomber) and Holden Ford (Mindhunter), explore criminal minds. Even the titles are somewhat reminiscent. What is more, both shows are branded as ‘Netflix Originals’, albeit one of them only in some territories (Fig. 1).

In spite of that label, there are, however, significant differences not least in terms of the production histories of the two shows. While Mindhunter was originally developed for Netflix, Manhunt was produced for and aired on Discovery Channel before months later being picked up by the streaming service, which then labelled it “An Original Netflix Series” in various territories – including Scandinavia, Germany, and the UK.

Thus, the two shows were produced for very different consumption modes. The Manhunt episodes were originally aired on advertiser-funded, linear television at a weekly interval (though the first episode was made available online in advance to boost the premiere and the first two episodes premiered on the same day – August 1, 2017 (Lynch, 2017)). In contrast, and in keeping with Netflix’s standard practice, each of the first two seasons of Mindhunter was released at once (on October 13, 2017 and August 16, 2019 respectively) granting control of the consumption pace to the viewer (Fig. 2). These differences are reflected in the storytelling of the two shows.

The Norms of Traditional American TV Serials

In his seminal article “From Beats to Arcs: Towards a Poetics of Television Narrative” (2006), Michael Z Newman identifies a set of storytelling norms that American prime time serials on broadcast channels adhere to. According to Newman the “commercial logic” of advertiser-supported (and one might add linear) channels provide a set of constraints that have very much helped shape these norms. Clear act structure accommodates commercial breaks, a micro-level organization in short narrative segments (beats) not exceeding two minutes, dangling causes, and cliffhangers are employed to keep the viewers from changing the channel (2006), while a careful balance of episodic and serial plots appeals to both newcomers and regular viewers.

Obviously, some things may have changed since Newman wrote his article in 2006, and streaming services like Netflix operate with different constraints, as they rely on subscription funding rather than ad revenue. According to Amanda Lotz, subscription-funded streaming services “often […] dispense with characteristics of advertiser support such as writing episodes with a structure of commercial breaks at certain intervals” (Lotz 2020, p. 30). She does not cite any examples, however.

Moreover, as streaming services are quite similar in terms of revenue model to premium cable channels, which do not include commercials and rely solely on subscription, their handling of act structure should not be completely different. However, according to Kristin Thompson, the classical act structure “is not abandoned or radically altered.” (Thompson 2003, p. 51) in premium cable shows even if it may be “somewhat more flexible” (ibid). Presumably the reason for this is that the acts “give an episode a sense of structure [and] provide the spectator with a sense of progress and guarantee the introduction of new dramatic premises and obstacles at intervals.” (Ibid pp. 54-55). In short, act structure is a means to successful screenwriting (ibid).

Thus, the extent to which streaming will generally alter the norms concerning act structure seems to be still up in the air. On a more general level this is a fitting epithet of the narrative norms of streaming series. Lotz concludes that it is too early to identify streaming norms. Drawing on Allen and Gomery (1985), Lotz describes the streaming shows so far as a “blending of change and continuity” with room for “experimentation” (2020, p. 27).

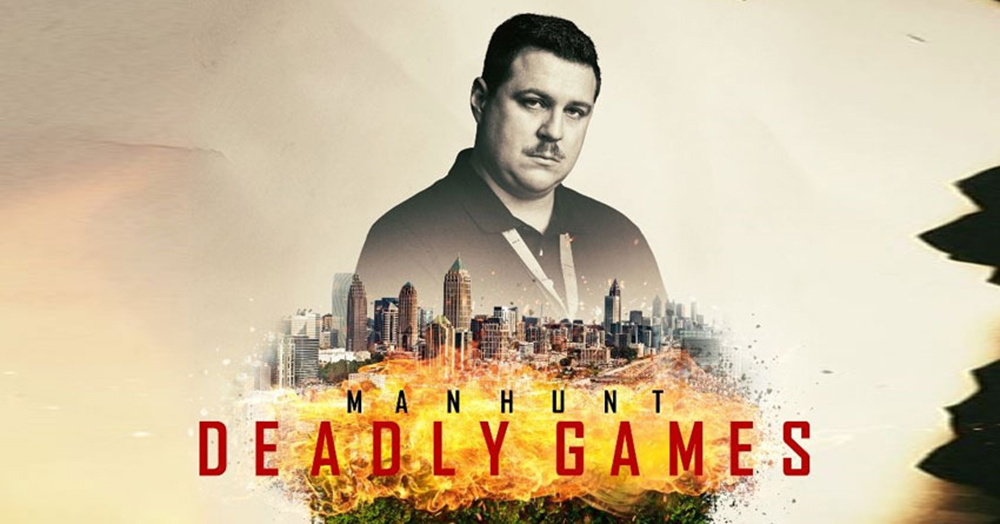

Still, some new norms seem to have materialized by now. Whereas linear TV channels have schedules that call for episodes of a particular length and a particular number of episodes per season (making it more valuable to “second market buyers”), VOD services have libraries (Lotz 2020) where such aspects are of little importance (ibid, pp. 29-30). The advent of streaming has also reinforced the trend that began with shows on premium cable channels like HBO towards increasingly fewer episodes per season (Barra 2017 and Lotz 2020). For the same reasons mini series and anthology series have also enjoyed a revival (Lotz 2020, p 29; for additional reasons for this development, see Langkjær 2020 pp. 193-194), and in this particular respect Manhunt: Unabomber, which is in fact the first season of an anthology series, actually seems a product of the trends brought about by VOD (Fig. 3).

The advent of VOD services, with their content libraries have also changed consumption practices. Rather than tuning into “this week’s episode”, new viewers will naturally begin with the first episode of the show. This may seem a trivial observation, but it means that the function of the episodic plot highlighted by Newman (see above) is irrelevant in this context as there are no (or very few) newcomers to cater to on a VOD platform. Moreover, viewers are likely to consume the episodes of a show at a faster pace. Already a fan practice enabled by DVD box sets, self-scheduling and binge-watching have now long since moved into the mainstream (Jenner 2017).

One of the consequences of these changing viewing patterns is a slight shift in the balance of the episodic and serial plotlines, towards the latter (Lotz 2020, p. 29). Citing shows like Breaking Bad (AMC 2008-2013), Homeland (Showtime, 2011-2020) and Game of Thrones (HBO, 2011-2019), Romano has described this development as a move from “open-ended” to “hyperserial” (Romano 2015). One should not exaggerate this shift, however, as the episode, organized in acts, continues to be a mainstay of serialized TV drama. Episodic plots are still very prominent in most shows regardless of platform, including Netflix. To take one example, each episode of Orange Is the New Black, one of Netflix’s early flagship shows, focuses on the backstory of a particular inmate (or guard) thus underlining the episode as a singular unit in the ongoing narrative whole.

Manhunt: Unabomber – geared to its original viewing context

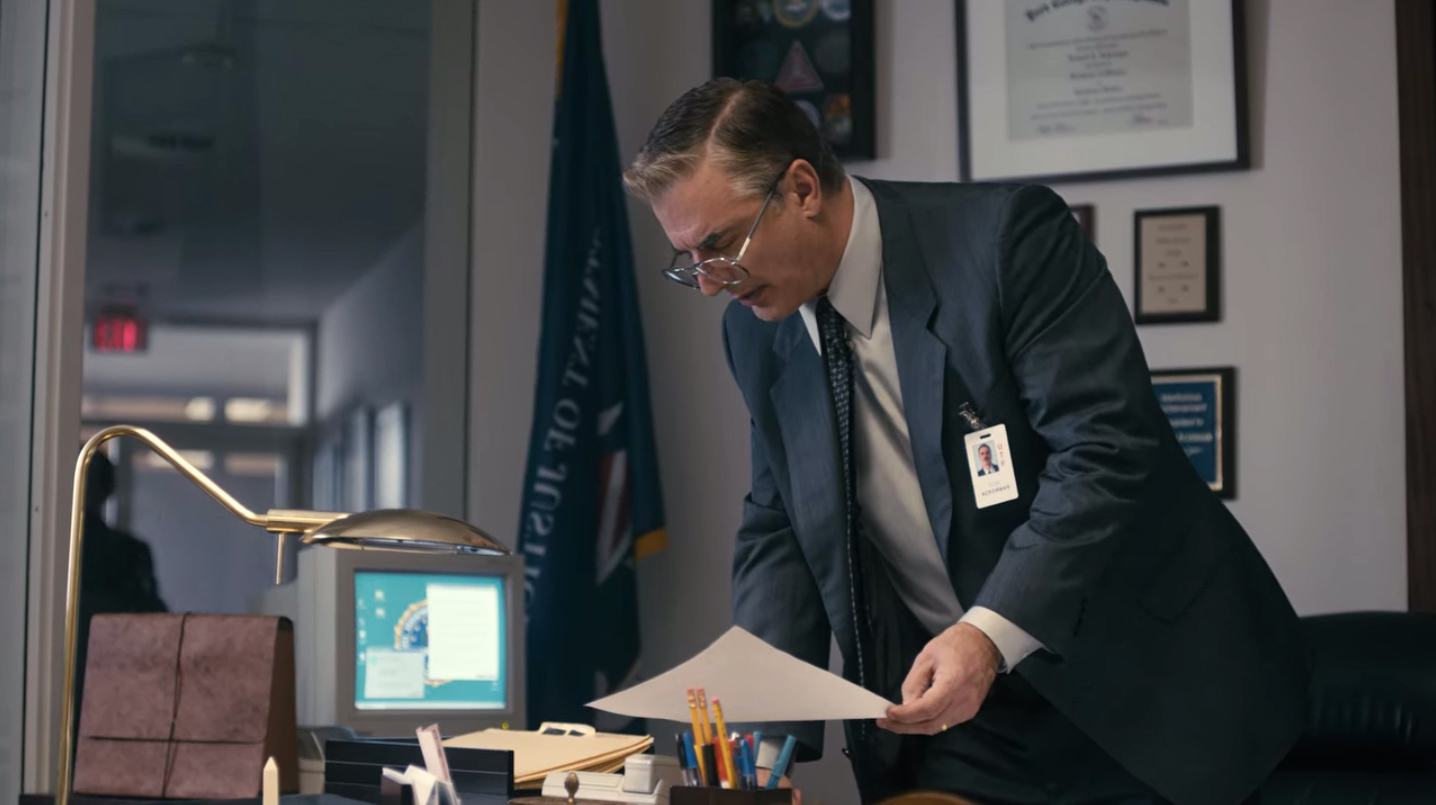

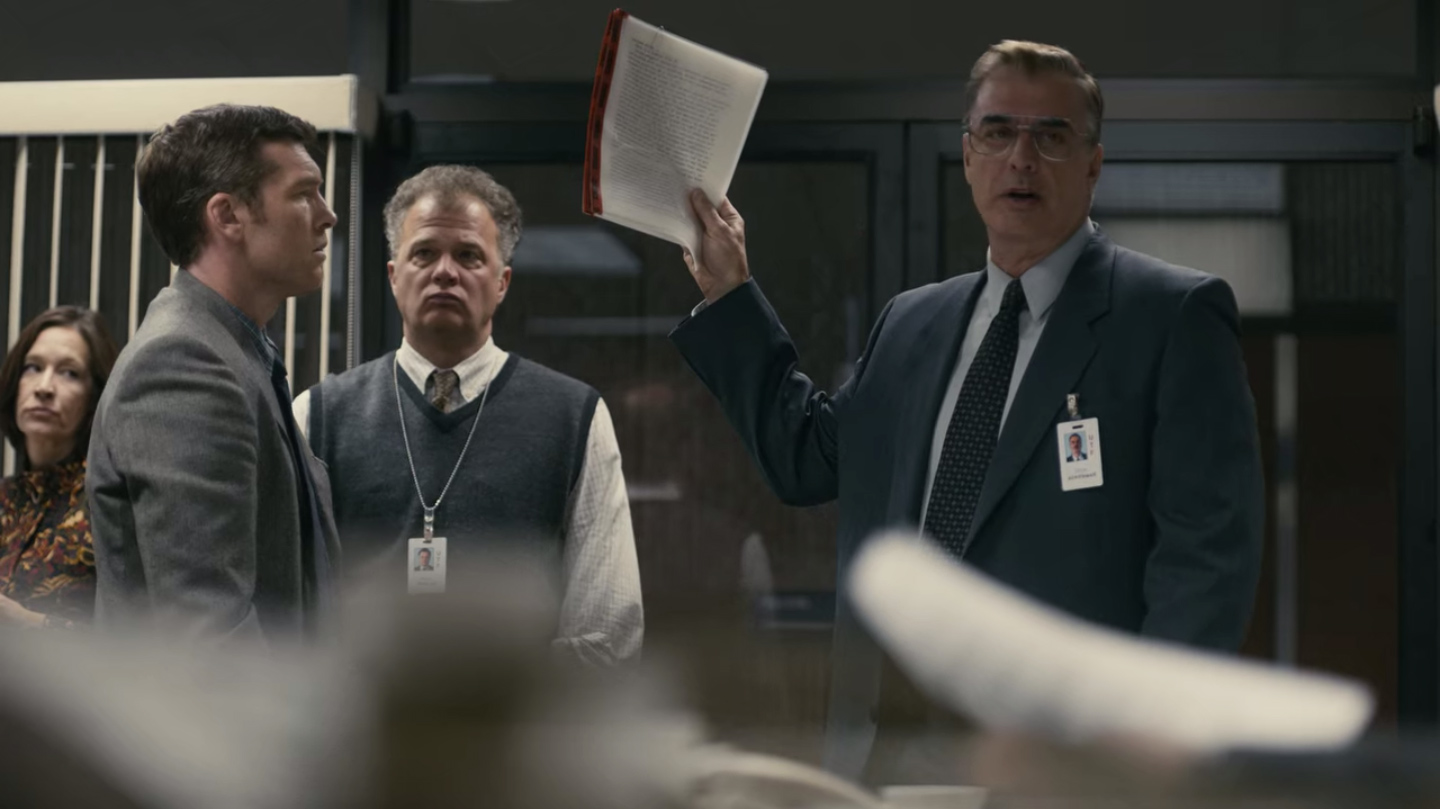

Manhunt: Unabomber certainly adheres quite closely to the norms identified by Newman. Discovery channel is actually a basic cable channel, but since it also includes commercials, Manhunt: Unabomber is informed by practically the same constraints, and it is clearly geared to appeal to viewers in the particular viewing context of linear (and advertiser-funded) television. Thus, all the episodes of Manhunt: Unabomber are organized in beats that generally do not exceed two minutes and employ a very clear act structure that makes room for commercial breaks with each act ending on a prominent cliffhanger (Fig. 4).

As Netflix does not have commercial breaks in their content, Scandinavians may feel somewhat perplexed when watching the alleged ‘Netflix Original’ Manhunt: Unabomber and noticing the fades to black that indicate the exact placements of commercial breaks. Obviously, this is a minor distraction, and in fact, some viewers might not even notice these fades. After all, there are countless shows on Netflix which were originally produced for advertiser-supported TV channels (e.g. Breaking Bad (AMC 2008-2013), The Americans (FX 2013-2018), Sons of Anarchy (FX 2008-2014) and How to Get Away with Murder (ABC 2014-2019)) so commercially informed storytelling including fades to black is quite common on Netflix.

What is arguably more conspicuous than the fades to black is the degree of narrative redundancy in Manhunt: Unabomber. Including recaps of important story information is part of the tried-and-tested formula of successful television writing – at least when writing for broadcast network channels (Thompson 2003, pp. 64-68). Such redundancy can pertain to information from previous episodes that the viewer needs to be aware of, but many recaps actually remind viewers of story information previously conveyed in the episode they are watching. The latter phenomenon is especially prominent around the commercial breaks. As these breaks interrupt the flow of an episode and are likely to break the viewer’s concentration, a large degree of redundancy is called for immediately after a break to get the viewer back on track.

Extensive redundancy

Manhunt: Unabomber employs such recapping extensively. “Episode 2: Pure Wudder” offers some of the best examples that while such recapping works well and serves important purposes on linear advertiser-supported TV, it seems oddly out of place and heavy-handed when watched as ‘original content’ on a streaming platform.

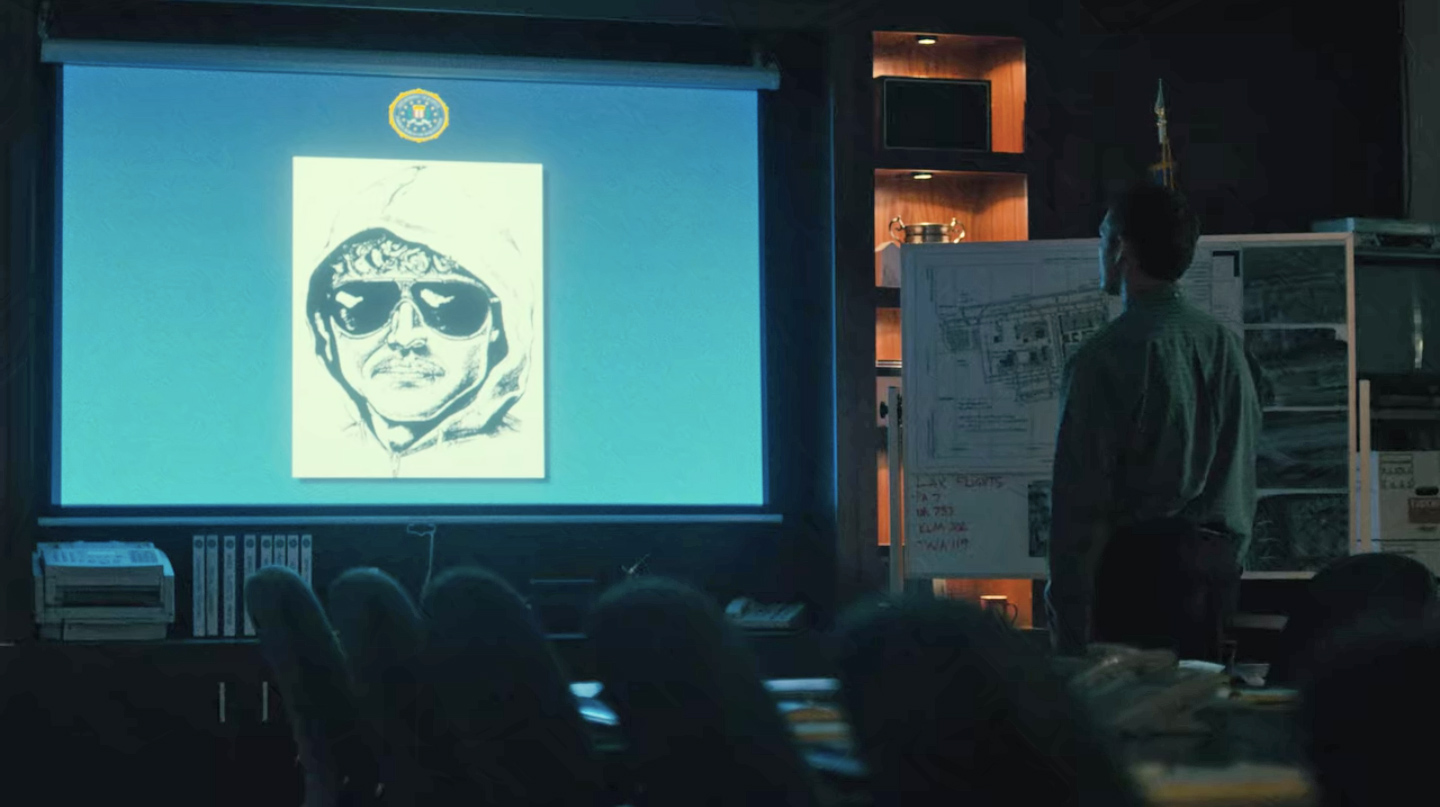

In this episode, the FBI receives two mutually contradictory letters from the Unabomber. In the first letter, he announces his intentions of blowing up an airplane causing a shutdown of the LAX Airport. However, the Bureau soon receives a second letter stating that the threat was only a prank. Fitz, who has been sidelined by his superiors, is now assigned the near-impossible task of deciding which letter to believe and hence if LAX can reopen for business. The episode thus establishes a very clear goal for our main character (making the right call) with incredibly high stakes and a specific deadline. Reminding the viewer of this dilemma and the high stakes obviously contributes to the suspense, but watched without commercial breaks, the redundancy seems excessive.

First, the viewer’s interest is piqued by the reaction made by Fitz’s superior Don Ackerman upon receiving the second letter: “Is this guy jerking us around or what?” (14.15). The dilemma and the terrible stakes are then immediately revealed as the episode (via a sound bridge of Ackerman reading the new letter aloud) cuts to Ackerman explaining the content of the second letter to a superior on the phone. In disbelief, the superior asks if the new letter really says that the threat is a prank, which Ackerman confirms allowing the scene to repeat this information twice (14.20) (Fig. 5).

In the next scene, Ackerman interrupts the meeting Fitz is in, dismisses Fitz’s plea that they start focusing more on the Unabomber’s manifesto and explains the situation (Fig. 6). I shall include Ackerman’s elaborate explanation in its entirety, as it is in itself redundant:

“The Unabomber has threatened to blow an airplane out of the sky. I’ve got four senators and Janet Reno on my call sheet, asking me whether to believe this letter, where he says he is going to kill a few hundred innocent people, or this one, where he says the bomb threat is just a prank. So I’m not reading anything else. I’m reading this [the letters] and trying to decide whether LAX can reopen for business, and if I make the wrong call, a few hundred people are gonna be blown out of the sky. [Turning to Fitz] So give me a profile that answers that question. If not, [pointing to the manifesto] that’s a stack of papers. These [the two letters] are human lives. Got it?”

(Manhunt: Unabomber 1.2. “Pure Wudder”, 15.30)

When approached by his assistant, Tabby Milgrim, in the following scene and asked what they are going to do about the manifesto, Fitz gets an opportunity to repeat the dilemma of the two letters and explain to her that the manifesto will have to wait. In addition to recapping the crucial dilemma, this serves two narrative purposes (Fig. 7).

Firstly, it makes clear to the viewer that Fitz has now accepted the near-impossible task he has been assigned. Secondly, it shows the viewer that figuring out if the bomb threat is a prank or not is also the top priority for Fitz. Answering this question will eventually earn Fitz the respect of his superiors and colleagues and thus help him achieve a longer-term goal, but earning the respect of his colleagues, or catching FC for that matter, it is not his primary goal in this episode, nor the main concern for the viewer. Establishing these vital premises for the plot, Fitz’s repetition of the dilemma marks the end of the second act, and with the big question of whether Fitz will manage to find the right answer serving as a strong cliffhanger we get the fade to black to make room for commercials.

“Is there a bomb on the plane, FC, or is it a prank?”

After the break, the resolution is postponed and hence the suspense is prolonged, as the episode does not immediately pick up the “bomb on a plane or a prank” plot line. Instead, this, the third, act starts with a scene in the other timeline of the show many years later when Fitz is going to meet the now incarcerated FC, aka. Ted Kaczynski, again. At this point, the two time lines have long since been carefully established so the viewer is not confused by this shift in time.

In this scene, where Fitz is in a car with Nathalie, the viewer learns that Fitz cannot dismiss the thought that maybe FC is right about the world. Though letting the hero see eye to eye with a terrorist, especially an authentic one like the Unabomber, may be quite daring, it merely demonstrates that while very classical in terms of it narrative choices, Manhunt: Unabomber also contains some of moral complexity that was introduced by the seminal HBO drama shows of the late 90s and early 00s and remains associated with quality TV (Halskov and Højer 2009 and Højer 2011). What is more, it is not really at odds with the traditions of the detective genre. Thus, it is possible to identify a virtual cluster of interrelated tropes concerning the connection between detective and killer – the fundamental similarity between the two characters, the special bond between them, and the idea that to catch a killer you must become (like) the killer, etc. (Bastholm 2016) – and it would seem that Manhunt: Unabomber employs most of them. Incidentally, this actually constitutes yet another similarity with Mindhunter, as this show also buys into at least some of the same tropes.

After this digression, the next scene takes us back to 1995 and Fitz trying to decide which letter to believe. The connection between the Fitz and the Unabomber is also prominent in this scene and thus provides narrative cohesion across the two timelines, as Fitz now addresses FC directly in his internal monologue. This voice over of his starts: “Is there a bomb on the plane, FC, or is it a prank?” (18.52) (Fig. 8).

Despite being repeated and emphasized over and over again in the previous act, the interruption of commercials makes such recapping of the central conflict a prudent strategy. However, if watching the show on Netflix, there is no forced break, and only approximately two and a half minutes have passed since the last enunciation of the dilemma, making this recap seem excessively redundant and trite even if the episode is generally effective.

The clear act structure in Manhunt: Unabomber

Having established that in terms of its use of recapping and narrative redundancy, Manhunt: Unabomber is very much a product of its original consumption mode, let us now turn to its use of act structure. Newman describes the typical act structure this way: “Television dramas introduce problems in the first act and end it with a surprise. Characters respond to complications caused by this surprise in the second act, see the stakes raised in the third act and resolve the problems in the fourth act” (Newman 2006, p. 21).

With one modification, this is an apt description of the episodes of Manhunt: Unabomber. Once again Episode 2: “Pure Wudder” may serve as an example. The first letter arrives five minutes into the first act, and the second letter arrives to complicate things in the second act. The third act sees the stakes raised as Fitz concludes that it must be a prank and convinces his superiors to advise Janet Reno to reopen LAX. In this case, the “problem” is resolved in the third act too as it turns out that Fitz’s call was indeed the right one. The reason for this early resolution is that the final act is devoted to Fitz’s investigative work to find the Unabomber and his meeting with the UNA-bomber two years later. The act ends moments before this meeting, creating a strong cliffhanger.

Incidentally, this new purpose of the final act is a manifestation of the aforementioned shift in the balance of the episodic and serial plotlines, towards the latter. Rather than resolving the main conflicts of the episode, the final act often introduces new complications and sets up cliffhangers. Examples of shows that use final acts in this manner include The Americans (FX 2013-18) and How to Get Away with Murder (ABC 2014-2020) (Fig. 9).

The final act is instead dedicated to what is to come: The latent gap between Elisabeth and Philip is stressed by means of a flashback to their first hours in the US and the revelation to the viewer that Elisabeth has repeatedly reported about Philip to her KGB superiors. In the very last scene of the episode their new neighbour, FBI agent Stan Beeman, breaks into their garage to examine the trunk of the car, where Timoshev was hidden. He does not find any evidence however, and the confrontation between Philip and him is thus postponed.

Ultimately, what matters more than the exact placement of the resolution is the use of specific goals and problems, high stakes and time pressure. “The most common units of television storytelling, episodes of television are constructed into patterns of problem/solution: a central conflict each week allows for some closure while a greater problem may still exist.” (Booth 2011, p. 372). Manhunt: Unabomber certainly adheres to such patterns even if episodic closure is achieved earlier and the final acts provide more ‘re-opening’ than closing.

Enjoying a different kind of freedom: Mindhunter

In contrast to Manhunt: Unabomber, Mindhunter was produced specifically for Netflix, and in various ways, it exploits the freedom of not being tied to a linear TV schedule. One obvious manifestation is the great variation of episode length – the episodes of Season 1 range from 34 (Episode 1.6) to 60 minutes (Episode 1.1) while season 2 has episodes ranging from 46 (Episode 2.2) to 73 minutes (Episode 2.9). Also worth mentioning is the unequal numbers of episodes of the two seasons (10 and 9 respectively).

Compared to Manhunt: Unabomber, the narrative pace of Mindhunter is quite slow. Because the narrative point of view is tied to Holden Ford, there is no cross-cutting back on forth between different plotlines. Another thing that contributes to the languid narration of Mindhunter is a general disregard for the tradition of short beats. Thus, dialogue scenes are allowed to play out for much longer than two minutes, most notably perhaps Ford’s first meeting with Kemper. Starting from the moment when the guard who escorted Kemper to the visiting room leaves, the conversation lasts for nearly nine minutes, only punctuated after approximately seven minutes by a cut to a very brief scene with Tench on the golf course, which does not really qualify as a beat of its own.

Since the interviews with the serial killers constitute what we might call the ‘money shots’ of the show, it may not be so surprising that they are generally allowed to go on for up to ten minutes. However, also other dialogue scenes are allowed to exceed the two-minute mark by a substantial margin. For instance, when Tench and Ford go see Dr. Wendy Carr to get her feedback on the project at the beginning of Episode 1.3, the conversation at her office lasts more than four and a half minutes (Fig. 10).

Another thing that sets the two shows apart is that Mindhunter is much less focused on problem/ solution and relies a lot less on deadlines than Manhunt: Unabomber. In a Sight & Sound interview with Fincher, Simran Hans describes Mindhunter as not having “the ticking-clock quality of his [Fincher’s] police procedurals” (Hans 2017, p. 36). While I actually struggle to see any ticking-clock element in Zodiac (2007), the element is obviously prominent in Fincher’s breakthrough police procedural Se7en (1995), and the absence of ticking clock is certainly a central characteristic of Mindhunter’s narration.

Drawing on Rick Altman’s syntactic approach to genre (1986) Grodahl has described the structure of the detective genre, and by extension the police procedural, as progressive-regressive in the sense that the plot progresses as the detective investigates the case, but at the same time this investigative work consists of moving backwards – uncovering past events (2003, pp. 197-198). Police procedurals and detective films obviously also include suspenseful elements that point forward in time – for instance deadlines, chase scenes, and last minute rescues.

However, Mindhunter focuses almost exclusively on past events both when Ford and Tench interview killers about what led to their crimes and the ongoing cases on which they assist local police departments. In these cases, where they are actually hunting obsessive killers, who are going to kill again, there is little time pressure involved.

No race to catch the killer, before he kills again

Significantly, the hunt is never really presented as a race to catch the killer, before he strikes again. Even in Season 2, which devotes several episodes to the investigation of the “Atlanta child murders”, the time pressure is not prominent. During the investigation, more dead bodies are discovered as the killer continues his killing spree, but we never meet the victims before they are killed, and thus there is little viewer involvement in their individual fates. Nor do we get a sense of foreboding that a new murder is soon going to be committed.

The opening scene of Episode 2.4 even mocks the standard thriller trope in which the murder victim is approached by the killer and because of his/her ignorance of the danger he/she is actually in walks right into the killer’s trap. In this scene before the opening credits, we actually see an African-American man, whom we cannot identify, driving alongside a young boy trying to lure him into the car by promising him money and taunting him for being afraid (Fig. 11).

Eventually, the boy gets in the car, and there is a fade to black and then opening credits. The scene initially comes across as effective in its use of suspense (even if not terribly original). After the title sequence, however, it is revealed that the driver is in fact a police officer, who was merely testing whether it would be possible for an African American man to lure kids into his car. In other words, by means of this red herring, Mindhunter distances itself from this traditional suspense trope (Fig. 12).

Mindhunter and act structure

Also in terms of act structure, it would seem that Mindhunter goes about it in a slightly different manner. For one thing, it often deviates from Newman’s point about the problems being introduced in the first act. Instead, since the narrative point of view especially in Season 1 as previously mentioned is generally closely tied to Holden Ford, problems and criminal cases are only introduced to us when he learns about them. Similarly, with the exception of The BTK Strangler, whom we meet in the ominous ‘cold opens’ (Coulthard 2010) of episodes 1.2-7, 1.9, 2.1-3, 2.5-6 and 2.8 a and the equally ominous closing scenes of Episode 1.10 and 2.9, we only learn about the serial killers when Ford becomes aware of and takes an interest in them. In other words, Mindhunter does not include any early scenes featuring the incarcerated serial killers to pique our interest before Ford and Tench interview them.

To take one example of a late introduction of a problem we may turn to Episode 1.4 and the ‘Beverley Gene case’, which is only introduced to us approximately 28 minutes into the 54-minute episode when they are approached by the local cop Mark Ocasek. The introduction of the case serves as a prominent turning point that divides the episode in two neat halves. One might argue that the first half provides Tench and especially Ford with insights that will inform their subsequent investigation. These would include details from their interviews with Montie Rissell and, on a personal level, Holden’s frustration when discovering that his girlfriend, Debbie, has other priorities than him when he wants her to make a long drive to go and pick up Tench and him after they have been in a car accident. However, nothing in these preceding 28 minutes hints at the case or prepares the viewer for the shift from the research of the first half to the investigation in the latter half.

To go back to the scenes featuring BTK, Lisa Coulthard offers the following definition of the cold open: “a pre-credit teaser that is not necessarily or directly tied to the action of the episode itself, but is rather an attraction on its own terms aimed at catching an audience quickly and convincing them to stay” (Coulthard, 2010). What is important to note about the Mindhunter’s cold opens featuring BTK is that they are attractions on their own terms, and, furthermore, that it gradually becomes clear to the viewer that although Ford and Tench are aware of BTK, the scenes with BTK are generally unconnected to the action of the episode or the season for that matter. Insofar as they anticipate future plot development, they point much further ahead and merely emphasizes the languid narration of the show (Fig. 13).

If we recall Lotz’s description of the streaming norms as a not yet clearly defined blending of continuity and change with some room for experimentation, it seems that Mindhunter is more intent on experimenting with both act structure and beat structure than its predecessors.

Pilots

I would like to end this article by turning my attention to the beginnings, or perhaps more accurately the first episode of each show as the opening episodes and their inherent differences are illustrative of the very different narrative choices in Manhunt: Unabomber and Mindhunter.

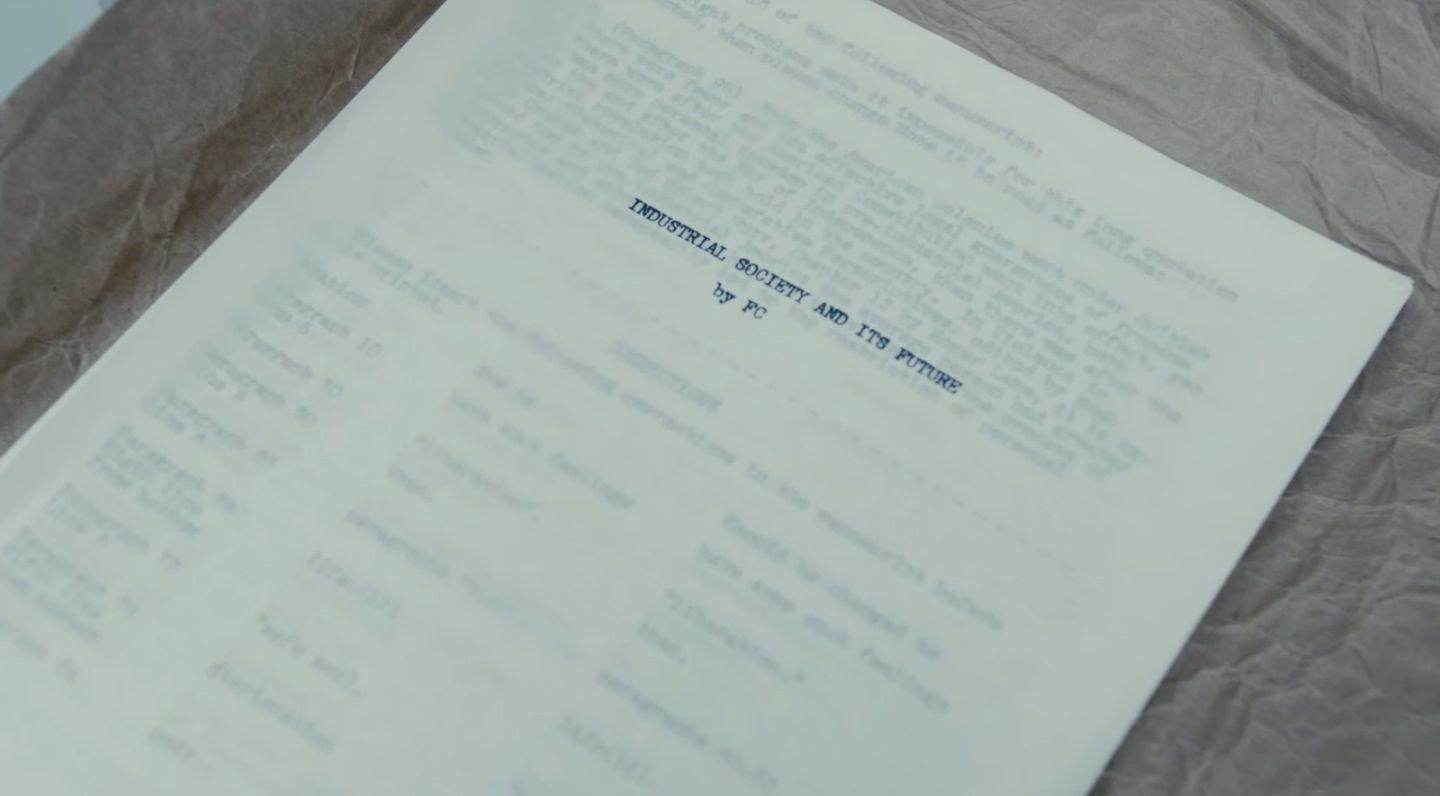

Manhunt: Unabomber episode 1 is in many ways a typical and fairly effective pilot. It manages to set up a lot of conflicts for the main character Fitz: work vs. family, finding the Unabomber, the lack of recognition from his superiors, and additionally it introduces no less than three potential romantic interests for him. The arrival of FC’s ‘Manifesto’ at the very end serves as a very strong cliffhanger, because the key to catching him must obviously be in there for Fitz to find.

The two different timelines are also introduced and they are skillfully employed to activate the viewer’s curiosity. Thus, we meet Genelli in 1995 and then, in a subsequent scene taking place in 1997, learn that according to Fitz he has “some nerve showing up”. Similarly, we meet Cole in 1997 and sense the hostility between Fitz and him, so when we subsequently witness their meeting in 1995 we know things will turn bad between them. Most importantly, of course, the marked change Fitz has undergone from well-groomed husband and father in 1995 to bearded recluse in 1997 provides a hint to the viewer that Fitz will not go through the investigation unharmed (Fig. 14).

Thus, the pilot episode is to use Mittell’s terms both “educational” (teaching us the narrative norms of the show, in this case the occasional shifts between the two timelines) and “inspirational” (making “us want to keep watching”) (Mittell 2015, p. 58).

Yet, even if the pilot episode of Manhunt: Unabomber is ultimately defined by the narrative norms of its original consumption mode, it is in many ways quite similar to the pilot episodes of at least early Netflix Originals. This may be surprising as on several occasions, Netflix executives and writers of Netflix shows have stressed that they do not attribute as much significance to the first episode of a show as is most often the case on linear television (VanDerWerff, 2015). What is more, Netflix does not request pilots as it is standard policy to commission an entire first season right away (Adalian, 2018).

This is part of a more general argument championed by chief content officer Ted Sarandos that shows produced for the Netflix consumption mode enjoy an unprecedented artistic freedom “such as the lack of a need for recaps or forced cliffhangers” (referred by McCormick, 2016). In their handling of the opening episode, series produced for Netflix are free to play the long game instead of frantically making sure to hook viewers from the get-go.

However, since stressing the novelty of one’s product is rarely bad for business, we should not accept Sarandos’s account too uncritically. It may be that Netflix orders whole seasons right away instead of asking for a pilot first, but upon closer inspection, it turns out that the opening episodes of early Netflix shows, such as House of Cards, Bloodlines, Orange Is the New Black, and Stranger Things, are rather classical pilot episodes intent on hooking the viewers from the first episode with immediately engaging teasers, strong episodic plots and potent cliffhangers. For instance, Episode 1 of Orange Is the New Black brings its fish-out-of-water main character Piper to the breaking point before in the closing scene confronting her with Alex, the woman whose testimony sent her to prison and who will remain her main love interest for the duration of the entire show (Fig. 15).

This brings us back to Lotz’s description of streaming norms as a not yet clearly defined blending of continuity and change. Even if changing distribution and consumption of VOD are “generative mechanisms” (Gomery & Allen 1985) for formal developments, the actual Netflix series may – to use Bordwell’s terminology, generally “repeat” just as much as they “revise, or reject” (Bordwell 2008, p. 22) the norms of their linear forerunners and counterparts. A likely reason for more continuity than change when it comes to the nature of the ‘pilots’ is that most of the creators of Netflix series have their backgrounds in network and cable shows.

Mindhunter 1.1

As should be clear by now, Mindhunter revises many of the storytelling norms of TV series. In this connection it is interesting to note that Fincher rejected the first script that executive producer of the series, Charlize Theron, who also introduced him to the project, presented him with. In a Q&A at the BFI London Film Festival in 2017, Fincher commented on the rejection of the first script:

“the script was by a very talented television writer, and it was nothing that I related to in terms of the story and in terms of how the story was laid out […] I was like I think I know how to do this, but I don’t want to do this […] so we found Joe Penhall, who she had worked with on The Road, and he came in and we kind of talked about what it could be, […] and he came back with a pitch that was pretty much the only way to do this”.

(Pierce, 2017)

One can only speculate about the extent to which the first script stuck to the established norms of serial TV drama, but the decision to bring in Penhall, who had no previous experience writing TV series, let alone American TV series, is not only remarkable, it may also provide some of the explanation why Mindhunter seems less bound by the narrative traditions of American TV series.

The suspenseful and dramatic opening scene of Mindhunter 1.1 certainly hooks the viewer and may seem a typical first scene of a pilot. Moreover, as the hostage-taker’s sudden society spawns Holden Ford’s desire to understand the pathological mind, the scene also introduces the main conflict of the show. However, after this scene, the already-mentioned “absence of a ticking-clock quality” becomes pronounced, as he does not know how to go on with his professional life. He ends up teaching at Quantico, which allows him to pursue his interest in criminal psychology, but his students and his superiors are unimpressed by his ideas and approach.

In line with Fincher’s general fondness of exposition (Zhou, 2014), the episode (together with the subsequent one) offers “a witty, thoughtful pop psychology introduction to behavioural science” (Hans 2017, p. 36). As part of this, he meets Professor Rathman, his new girlfriend Debbie, and Tench, all of whom offer some early insights on criminal psychology for him and us, but he is still very unsure about how to proceed. David Fincher has commented on this particular aspect of his main character, which he sees as “more cinematic than televisual” (ibid):

“Ford doesn’t know [how to do his new job]. He has an instinct that something’s amiss, and that he’s somehow underqualified for the task he’s been assigned, and I liked that. In television, you mostly need the expert. It’s a very odd place to begin winding the audience up, because for the most part people want to go, “Well is this the guy who’s gonna get me there or not”?

(Fincher quoted by Hans 2017)

Ford and Tench are presented with a case, but not before 50 minutes into the episode (total running time: 57.30), and as they are unable to crack the case, it mainly serves to make clear to Ford that they do not know enough about serial killers. Significantly the case does not serve as an episodic plot with clear-cut goals and narrative closure (Figure 16).

Playing the long game

The most conspicuous aspect of Episode 1 is that Ford does not meet Ed Kemper – he does not even conceive the idea to interview him. Not only do the interviews with the serial killers constitute the central premise of Mindhunter, which in itself would make the decision not to include this element in Episode 1 remarkable, the viewers are also likely to know about this premise before watching the first episode, since the promotion material – e.g. the first trailer – has naturally emphasized the interviews (Figure 17).

In continuation of this, it is also worth noting that Mindhunter chooses not to employ the popular device described by Mittell “of starting a pilot at a moment of climax and looping back to explain how we arrived at this point” (2015, p. 61). Using this device would have allowed the viewer to see part of the first interview (or alternatively Ford’s breakdown at the end of Season 1), and would have been in line with traditional pilot strategies of hooking the viewer.

In contrast to the aforementioned Netflix Originals, Mindhunter actually exploits the freedom brought about by Netflix’s VOD model in its handling of the first episode, which largely disregards the typical norms of pilots. Instead, it focuses on actually playing the long game. Doing this it is clearly banking on more patience from its viewers than a drama series on a linear TV channel, such as Manhunt: Unabomber, might be able to afford to – and notably most other ‘authentic’ Netflix Originals.

As we have seen, the willingness to exploit new narrative possibilities brought about by its VOD distribution is a recurrent feature in Mindhunter’s storytelling including the narrative pace, the varying episode lengths, and the act structure. In fact, Mindhunter seems to be less closely tied to the narrative traditions of linear TV series than at least the early drama series made specifically for Netflix. This makes the contrast to Manhunt: Unabomber, a show clearly made for its original linear platform, even greater. Thus, the two shows about serial killers and profilers that were launched as original content on Netflix demonstrate how viewing contexts shape storytelling strategies.

Facts

Manhunt: Unabomber is not the only series to premiere on another channel before being picked up by Netflix and branded as a “Netflix Original”. Other examples include The Alienist (2018-), which airs on TNT in the US with Netflix having acquired the international rights, the British mini series Bodyguard (2018), which premiered on BBC One but is distributed internationally as a Netflix show and even includes “previously on” sequences when watched on the streaming platform , and the true crime series The Staircase (2004-2018). As regards the latter, the case is a bit more complex as the first 10 episodes were produced for French channel Canal+, while the last three episodes, which came 14 years later, were commissioned by Netflix.

Series

- The Alienist (Caleb Carr, TNT 2018-)

- The Americans (Joe Weisberg, FX 2013-2018)

- Bloodlines (Todd A. Kessler, Glenn Kessler, and Daniel Zelman, Netflix 2015-2017)

- Bodyguard (Jed Mercurio, BBC One 2018)

- Breaking Bad (Vince Gilligan, AMC 2008-2013)

- Dexter (James Manos Jr., Showtime 2006-2013)

- The Fall (Allan Cubitt, RTÉ One / BBC Two 2013-2016)

- House of Cards (Beau Willimon, Netflix 2013-2018)

- How to Get Away with Murder (Peter Nowalk, ABC 2014-2020)

- Manhunt: Unabomber (Andrew Sodroski, Jim Clemente, and Tony Gittelson, Discovery Channel 2017)

- Manhunt: Deadly Games (Andrew Sodroski, Jim Clemente, and Tony Gittelson, Spectrum 2020)

- Mindhunter (Joe Penhall, Netflix 2017-2019)

- Orange is the New Black (Jenji Kohan, Netflix 2013-2019)

- Sons of Anarchy (Kurt Sutter, FX 2008-2014)

- The Staircase (Jean-Xavier de Lestrade, Canal+ 2004-2013/ Netflix 2018)

- Stranger Things (The Duffer Brothers, Netflix 2016-)

Films

- Silence of the Lambs (Jonathan Demme, 1991)

- Se7en (David Fincher, 1995)

- Zodiac (David Fincher, 2007)

Literature

- Adalian, Josef (2018): “Inside the Binge Factory“, in Vulture 10 June, 2018.

- Allen, Robert & Douglas Gomery (1985): Film History. Theory and Practice, New York, McGraw-Hill

- Altman, Rick (1986): “A Semantic/Syntactic Approach to Film Genre” in Barry, Keith Grant (1986/1995, 2003): Film Genre Reader III, University of Texas Press, Austin

- Barra, Luca (2017):”Master of None, Atlanta, and Audience Engagement in Contemporary US TV Comedy“, in 16:9, November 19, 2017

- Bastholm, Søren Rørdam (2016): “Det gyselige og der ordinære: The Fall” in 16:9 3 February, 2016.

- Booth, Paul (2011): “Memories, Temporalities, Fictions: Temporal Displacement in Contemporary Television”, in Television and New Media Vol.12, no. 4, 2011

- Bordwell, David (2008): Poetics of Cinema. New York and London, Routledge

- Coulthard, Lisa (2010): “The Hotness of Cold Opens: Breaking Bad and the Serial Narrative as Puzzle“, in Flowjournal, 12 November, 2010.

- Grodahl, Torben (2003): Filmoplevelse: en indføring i audiovisuel teori og analyse, Samfundslitteratur

- Halskov, Andreas and Henrik Højer (2009): “It’s Not TV…“, in 16:9 Issue 33, September 2009

- Hans, Simran (2017): Killer Instinct, in Sight & Sound November 2017

- Harris, Mark (2020): “David Fincher Confirms the ‘Very Expensive’ Mindhunter Is Done for Now“, in Vulture 23 October, 2020

- Højer, Henrik 2011: “De døde vandrer stadig“, in 16:9 Issue 42, June 2011

- Jenner, Mareike (2017): “Binge-watching: Video-on-demand, quality TV and mainstreaming fandom”, in International Journal of Cultural Studies, 2017, Vol. 20 (3)

- Langkjær, Jakob (2020):”Tilbage til fremtiden: Antologieseriens tilbagekomst i streamingens guldalder”, in Halskov, Højer, Korsgaard, Larsen and Nielsen: Streaming for viderekomne: Fra Doggystyle til Black Mirror og The Jinx, Via Film & Transmedia

- Lotz, Amanda (2020): “Storytelling in a World of Streaming”, in Halskov, Højer, Korsgaard, Larsen and Nielsen: Streaming for viderekomne: Fra Doggystyle til Black Mirror og The Jinx, Via Film & Transmedia

- Lynch, Jason (2017): “If Discorery’s Unabomber Series Is a Hit, It Could Launch a New Network Franchise“, in Adweek, 1 August, 2017,

- McCormick, Casey J. (2016): “Forward Is the Battle Cry”: Binge-Viewing Netflix’s “House of Cards”, in Kevin McDonald and Daniel Smith-Rowsey: The Netflix Effect: Technology and Entertainment in the 21st Century, Bloomsbury Academic

- Mittell, Jason (2015): Complex TV – The Poetics of Contemporary Television Storytelling. The New York University Press

- Newman, Michael Z (2006): “From Beats to Arcs: Towards a Poetics of Television Narrative”, in The Velvet Light Trap Number 58; Fall 2006

- Pierce, Nev (2017): “Mindhunter Q&A with David Fincher at BFI London Film Festival”, 10 October, 2017.

- Romano, Andrew (2015): “Why You’re Addicted to TV“, in Newsweek Magazine 15 May, 2015.

- Thompson, Kristin (2003): Storytelling in Film and Television. Harvard University Press.

- VanDerWerff, Todd (2015): “Ne

tflix is accidentally inventing a new art form — not quite TV and not quite film“, in Vox 30 July, 2015. - Zhou, Tony (2014): “Fincher – And the Other Way is Wrong“, video essay as part of Every Frame a Painting.