With the release of Memoria (2021) marking Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s first film outside his native Thailand, the unique cinematic fabric of a filmmaker concerned with conflicts between the mundane and the supernatural – the secular and the ethereal – crystallizes. And while defying religious categorization, the tenets of “Transcendental Style”: a genre of filmmaking concerned with portrayals of a spiritual Wholly Other, provides a possible entryway into the otherworldly realm of his cinema.

Along with dreamlike storyworlds, elliptical narratives, and slow, hypnotic pacing, much of the critical analysis surrounding Thai filmmaker Apichatpong Weerasethakul has centered on the supernatural forces that pervade his films – gently manifesting within otherwise realistic, everyday scenarios. In Memoria, we follow Jessica (Tilda Swinton) a Scottish expatriate in Colombia who is visiting her ill sister. Pursued by sudden manifestations of a loud “bang” sound, which recurs every now and then in her head, inspired by the director’s own experience with “Exploding Head Syndrome,” Jessica begins to try to make sense of her strange symptoms, enlisting the help of a sound designer to synthesize a recreation of the “bang,” as well as paying a visit to the doctor’s office in the hope of procuring a Xanax prescription. However, most of the film is devoted to vignette-like snippets of Jessica wandering around various environments, which range from the clinical research facilities of a hospital/university to the outdoor spaces of Colombian city centers and countrysides, often resulting in strange, singular interactions. In piecing these together however, what begins to emerge is an undercurrent of the ancient histories of the land around her, as well as a growing sense that the sound plaguing Jessica may be more than just a psychological condition, but something from beyond this world. And in the film’s final act: a single, unbroken interaction with a fish scaler in the countryside, Apichatpong and his character finally reach a spiritual breakthrough, and some answer to the origin of the “bang.”

A Religious Cinema

Spiritual matters have always been deeply embedded in Apichatpong’s work, with most of the critical focus directed towards the Buddhist influences in his films. However, given the director’s aversion to personal affiliations with any religion, it would be disingenuous to label him a religious filmmaker. Rather, as Alvaro Malaina describes the spirituality of his Thai work, “Apichatpong combines the sacred, supernatural, spiritual lines of flight with the profane, natural mundane lines of segmentarity that comprise the daily life of people in Isan, presenting complex assemblages” while, “rejecting any formal religious inscription” (2022, p. 145). Certainly, elements of Buddhism have served as inspiration for his storyworlds, and we even see hints of samsara in Memoria, in a scene (to be discussed later) where a local fish scaler recounts events from his previous lifetimes – most obviously drawing parallels to Apichatpong’s 2010 Cannes-winner, Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives. It is an influence that permeates his work and often forms its spiritual core, even as he moves his storyworld from Thailand to Colombia. As Apichatpong explains, “In the culture of Buddhism, there is a deep connection with spirits and animals. Even though I don’t believe in spirits, I think the idea of them has shaped me in some way… It makes you think about the abundance of things you don’t know (O’Connor, 2022, para 13). While Apichatpong may not be directly concerned with religious transcendence, it is clear that he maintains a strong transcendental interest. In fact, the release strategy of Memoria appears to play into these transcendental interests. One could almost be tempted to say that the exhibition of the film has been designed in a religious manner. The church-like devotion to physical screenings has already prompted some controversy when the film’s American distributor, Neon, elected to purposefully shun a streaming release in favor of having the film “travel” across various US territories, opening in different places at different times. And in Denmark, Grand Teatret has been running the film at two daily screenings at 9:30 am and 11:30 pm – time slots which seem to reflect the wake/sleep processes of the brain, almost implying a heightened state of experience. Given the distinctly cinematic, sensory, and indeed hallucinatory qualities that have become attributed to Apichatpong’s oeuvre, it seems only logical that the exhibition of his films be curated to best induce the visceral, transcendent responses, which lie at the heart of his method.

Transcendental Style

The word transcendental is one which I feel cautious about using in relation to cinema: whether it is the religious connotations, the pretentiousness which surrounds the term, or hackneyed manner in which it can become a catch-all phrase for any work that elicits a deep psychological response in the eyes of its beholder. Yet it feels appropriate for Memoria, and indeed for many of Apichatpong’s films – films that seem to evoke the distinct visceral effect of transcendence, “rearranging your own consciousness” (O’Sulivan, 2022, para 3). In his seminal academic work Transcendental Style, written when the now revered screenwriter/director Paul Schrader (Taxi Driver, Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters) was just a young graduate student at UCLA, Schrader coins the term to describe a style of filmmaking “which has been used by various artists in diverse cultures to express the Holy.” (Schrader, 2018, p. 35). In his book, Schrader analyzes the works of Robert Bresson, Yasujiro Ozu, and (to a lesser extent) Carl Theodor Dreyer – three titans of classic, arthouse cinema, each of whom he argues can be united under this transcendental style. The three main qualities Schrader identifies as shared between these filmmakers, and becomes necessary in transcendental style, are as follows.

- The everyday: “a meticulous representation of the dull, banal commonplaces of everyday living” (Schrader, 2018, p. 67).

- Disparity: “an actual or potential disunity between man and his environment which culminates in a decisive action” (Schrader, 2018, p. 70).

- Stasis: “a frozen view of life which does not resolve the disparity but transcends it” (Schrader, 2018, p. 75).

In recent discussions and re-evaluations of Transcendental Style, Schrader has made it clear that most cinema which may at first appear transcendental, is ultimately something else, most clearly pointing to slow-cinema as such an example. Apichatpong is certainly also a director who would fall into Schrader’s definition of a slow-cinema artist. Nevertheless, in these next few sections, I shall propose (almost certainly to Schrader’s chagrin) that Memoria embodies the key components of Transcendental Style, and goes some distance in describing the spiritual qualities that lie within his work. What should become evident is the way in which Apichatpong fuses these core elements of transcendental style with subject matter that is very much concerned with existential concerns of what could be described as a “Wholly Other,” although perhaps one very different to the God evoked by Bresson or Dreyer, and informed by Apichatpong’s own background and spiritual interests as an artist. After all, and to (very playfully) use Schrader’s own words against him, “There is no static-free communication with the Holy, and any work which expresses the Transcendent must also express the personality and culture of its artist” (2018, p. 52).

The Everyday

Memoria opens with a sustained shot of Jessica in her room, as she is first woken up at night by the loud “bang,” prompting her to get out of bed and search for its source. Accompanying this shot, and indeed the entire sequence of few, and lingering shots, is the diegetic sound of rainfall. It is a slow, dream-like entry into the world of the film, as typical of a filmmaker whose cinema “tends to anesthetize the audience” (Chulphongsathorn, 2022, p. 543). The medical metaphor is a fitting one, given that both of the director’s parents are doctors, and medical spaces occupy the visual space in most of his films, however I would also liken Apichatpong’s technique to hypnosis – slowly conditioning the audience to the particular rhythms of his sound and image, before working away at our subconscious. As with Bresson, Ozu, and Dreyer: the filmmakers discussed in Schrader’s Transcendental Style, Apichatpong’s form is one of minimalism. His camera barely moves, remaining fixed on his subjects for longer than what our conditioned brains perceive as necessary, or even logical, and keeps us at both a physical and emotional distance from the characters. In the absence of plenty, our mind is left to wander, to peruse the frame, the compositions, and mull over the morsels of action that are fed to us. And within this valley of silence, among the dream-like serenity of the film’s liquid shape, Apichatpong has already planted a seed of intrigue – a sensory element that becomes the pervasive undercurrent of the film: namely, the “bang.”

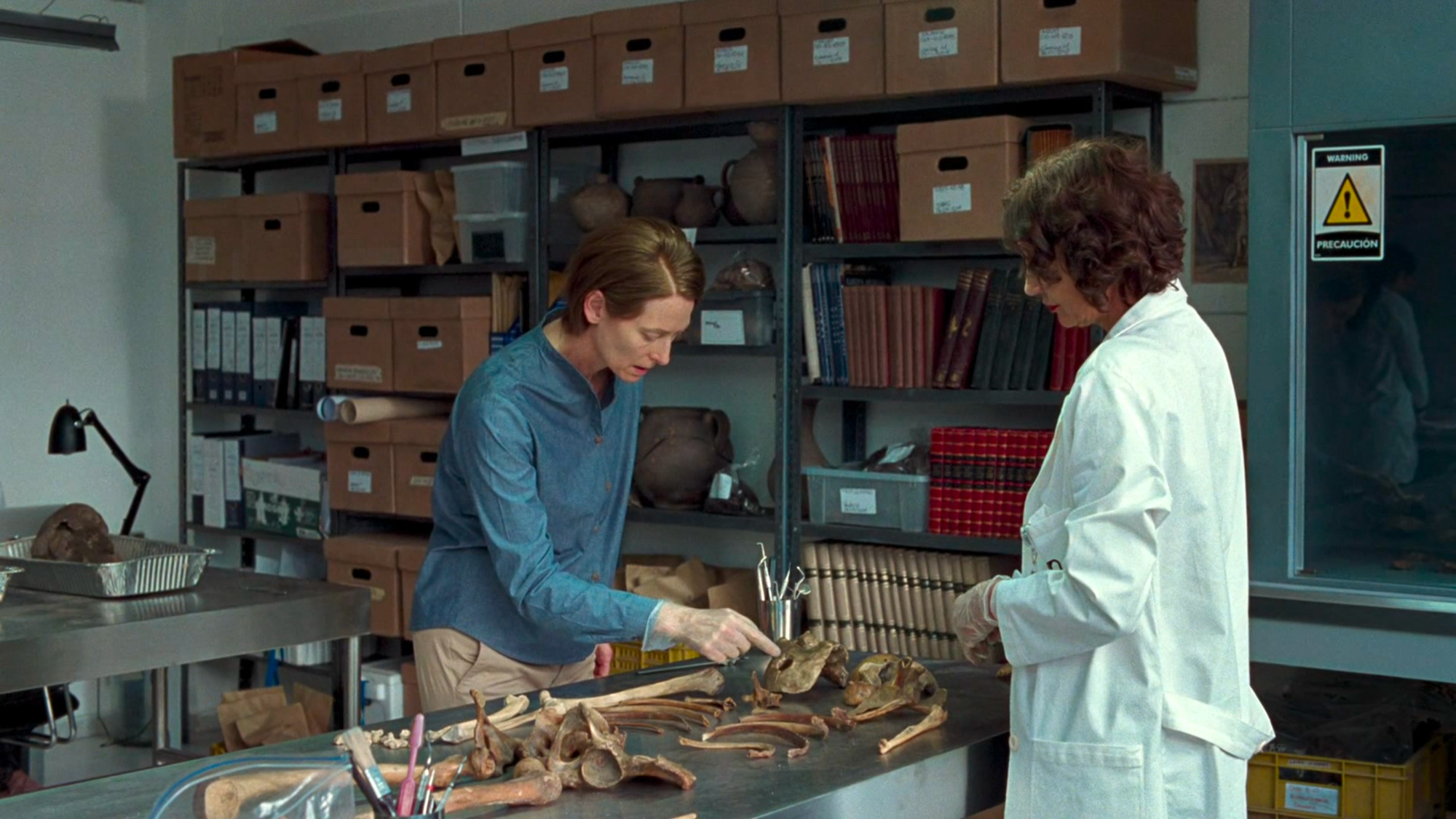

Throughout the first half of the film, this sound acts as the only guide for Jessica, and also our own sensory experience of the film. Everything else appears trivial. We wander from space to space, from one isolated interaction to the next, with no clear intent or purpose: the dull everyday as described by Schrader. Occasionally, the sound returns, providing a disturbance to both Jessica’s mental state as well as our own tranquil experience of the film. The bang, in this calm, naturalistic soundscape has a strange, visceral impact. It shakes us, before letting us return to the serene tempo of the film. Like occasionally being startled awake, before being allowed to drift back into sleep. Jessica almost appears to be sleepwalking through her everyday, as many of Apchatpong’s protagonists seem to do, haunted by the persistence of the sound in her memory. Nevertheless, it is within these seemingly trivial passages of the film that Apichatpong interweaves several thematic elements that will prove crucial to later revelations and the transcendence of the film. Paramount to this are discussions around an archaeology project being undertaken in an underground tunnel, which seeks to uncover the sociological histories of a Colombian tribe, and evoke the “excavation and reanimation of lost memories” (Chang, 2022, para 11). As revealed by Jessica’s brother-in-law, many people, including himself, believe the project to be cursed by the Amazonian tribe – and the cause of the illness affecting her sister who herself is working on the project – they do not seem to want to be disturbed. Combined with the mysterious “bang” (which also appears to stir the cars in the parking lot to unite in a choir of alarms), Apichatpong manages to incite a sense of supernatural activity, shimmering below the surface of the monotonous everyday, which in spirit with his work forms a “low-key but sustained dialogue with a place and a people” (Teh, 2011, p. 597).

Disparity

Eventually, transcendence arrives in the final act of the film – an act that appears to magically manifest from within the structure of the everyday we have been accustomed to up until this point. Seemingly in the aftermath of her encounter with a doctor in a rural village, Jessica passes by a stream where a local man is scaling a fish. She begins talking to him, and what follows is a sequence arguably even more stringent to the withholding techniques than those of the everyday section. This single scene, which takes up an incredible twenty minutes of the film’s two-hour runtime (excluding credits) features seven cuts, and an uninterrupted 8-minute wide-shot of the two characters slowly conversing. However, what begins as a fairly commonplace interaction suddenly veers into surrealism when the fish scaler claims to remember his past lives, and nothing less than the entire history of the universe, as well as implying alien roots, saying, “I remember… we were in space with the others.” To make matters even more puzzling – the man reveals his name is Hernán – the same name of the sound designer who helped Jessica recreate the “bang”, before disappearing from the story (Jessica’s subsequent attempt to track him down even implies he may never have existed). Hernán explains that these histories are felt in the vibrations in the Earth’s natural environment which “absorb everything”, picking up a piece of rock to demonstrate, as he recounts the story of a man who was robbed and beaten up by the very stream they are sitting at, saying, “It happened a long time ago, but the vibrations were embedded here, in this stone. This stone was part of the rock he was sitting on.” This is where the spiritual characteristics of Apichatpong’s film truly emerge. As Anders Bergstrom writes, Apichatpong’s work concerns itself with “the spiritual function of memory in global modernity,” where “memory marks a transcendence of a state of ignorance and the characters’ only hope of connecting with their past” (2015, p. 2-7). The alien characteristics of the man are further heightened, when after telling her that “our kind never dreams,” he lies down to fall asleep, after being prompted by Jessica to demonstrate this strange symptom. Here, the camera fixes on him in a rare close-up, staying on Hernán as he appears to die, the life suddenly leaving him as he lies motionless with eyes open, before abruptly waking back to life after a few minutes of uninterrupted movement. Back from beyond.

Transcendence Through Sound

The two then move to Hernán’s home, where he explains that his mind is like a harddisk, and Jessica an antenna – able to travel on the frequency of his memories. As the two sit together in another long sequence, the sound design shape-shifting through the memory bank of Hernán’s history of the planet, we suddenly arrive at the “bang.” A sound, which Hernán explains, was “before our time.” It’s a revelatory moment, both for Jessica and the audience, emphasized by her visceral reaction to the experience of having the sound appear once again, in this new context. The emotion is written across her face. It is Schrader’s decisive moment. “There is, in this stage, an inexplicable outpouring of human feeling which can have no adequate receptacle” (Schrader, 2018, p. 71). The effect is transportative – a well bursting open – a relief. Suddenly, we see the image of what appears to be a kind of spaceship, taking off from inside the Colombian jungle, and in forming some type of portal – incites the sound of the “bang.” It is a moment of transcendence, which links the film’s themes of memory with a deeper spiritual connection that mirrors Buddhist life cycles, although with a sci-fi spin. In doing so, Apichatpong underlines “the spiritual function of memory in global modernity,” where “memory marks a transcendence of a state of ignorance and the characters’ only hope of connecting with their past” (Bergstrom, 2015, p. 2-7). The experience of this incredible sequence is worth commenting on a little further. Having been a passenger to Apichatpong’s slow, hypnotic pacing of the “everyday” section of the film, albeit with hints at supernatural forces lurking beneath the clinical surface, the film’s final act is overwhelming – even mind-splitting. Certainly, the audience’s experience of these moments feels akin to entering some other sensory realm – a higher state of being. “The transcendental film director is a ‘spirit guide,” Schrader writes, who “seeks to escort the respondent to another level of consciousness, a Wholly Other world” (2018, p. 23). Apichatpong passes the test on all accounts.

Stasis

As Schrader proclaims, “The decisive action does not resolve disparity, but freezes it into stasis” (2018, p. 76). Apichatpong duly obliges. Following the decisive action – the moment of transcendence in which Jessica and the audience have been exposed to the Wholly Other – the film slows back down to complete stillness. What concludes the film is stasis – “the end point of transcendental style” (Schrader, 2018, p. 24). We remain in the awakened state of this transcendence, left to dwell in this heightened realm of knowledge. It is as if we, like Jessica, have been granted a space to float on the frequency of this holy wisdom – to tap into the memories of the Amazonian land and its people in a way that mirrors Uncle Boonmee’s ability to remember his past lives – his lucidity of Buddhist samsara. The last moments of the film are simple images of landscape. A collection of what, in Ozu’s hands, would be referred to as pillow shots. These shots, in another context, would simply amount to establishing shots. Transitions between visual spaces. Perhaps a pause to catch our breaths. However, like Ozu, Apichatpong uses them for transcendental means. In this context, on this new tangent of transcendental experience, the shots of landscape amount to more than that. With these images, our awakened minds are privy to all the stories harnessed within the land, and given the subconscious trajectory of the individual audience member, the memories of his own experiences too – lived or imagined. Over the final shots of the Amazonian landscape, we hear the words of a radio announcement, explaining that volcanic tremors have opened up areas in the excavation site previously inaccessible to the archaeology team, as the film finally cuts to black, leaving us waking in its magic spell.

Fakta

Film

- Memoria (Apichatpong Weerasethakul, 2021)

Litteratur

- Bergstrom, Anders. “Cinematic Past Lives: Memory, Modernity, and Cinematic Reincarnation in Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s ‘Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives.’” Mosaic (Winnipeg) 48.4 (2015): 1–16. Web.

- Chang, Justin. “Review: ‘Memoria’ Is One of the Greatest Movies You’ll See – or Hear – in a Theater This Year.” Los Angeles Times, Los Angeles Times, 7 Apr. 2022.

- Chulphongsathorn, Graiwoot. “Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Planetary Cinema.” Screen (London) 62.4 (2022): 541–548. Web.

- Malaina, Alvaro. “Assembling the Natural and the Supernatural in Thai Independent Cinema: The Ethno-Cinematographic Rhizomes of Apichatpong Weerasethakul.” Asian anthropology 21.2 (2022): 138–154. Web.

- O’Connor Film, Rory. “Apichatpong Weerasethakul on Why Cinema Should Be Communal.” Frieze, 19 Jan. 2022.

- O’Sullivan, Michael. “Review | ‘Memoria’ Is a Haunting, Transcendent, Unforgettable Film.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 5 Apr. 2022.

- Schrader, Paul. Transcendental Style in Film : Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press,, 2018. Web.

- Teh, David. “Itinerant Cinema: The Social Surrealism of Apichatpong Weerasethakul.” Third text 25.5 (2011): 595–609. Web.