This article is for anyone who would like to have a better grasp of the five types of voice-over found in such classics as Wings of Desire, Rashomon, and The Third Man. An original model presented in plain, jargon-free language with plenty of stills, full transcription of thoughts and spoken lines, and no filler or mystification.

Sarah Kozloff’s Invisible Storytellers: Voice-over Narration in American Fiction Film (1988) remains the best comprehensive work on the subject. It was a great improvement over Gérard Genette’s earlier discussion in Narrative Discourse. An Essay in Method (1980) in at least two respects: 1) Genette’s work was designed for literary study while Kozloff focuses on film; and 2) Genette uses such terms as homodiegetic, heterodiegetic, infradiegetic, extradiegetic and autodiegetic, the meanings of which can be difficult to disentangle and which Kozloff aptly characterizes as “tongue-twisting and obscure to the uninitiated” (p. 42).

However Kozloff’s otherwise excellent work does not in my view leave the reader with a clearly delineated typology. And her definition of voice-over is too narrow and restrictive: “oral statements, conveying any portion of a narrative, spoken by an unseen speaker situated in a space and time other than that simultaneously being presented by the images on the screen” (p. 5). My own more inclusive definition is also more specific and though lacking in the brevity usually prized in a definition, it can actually serve as an overview of the new typology proposed here.

Voice-over is here defined as consisting of either:

- inner thoughts of a character shown on screen with his or her lips not moving;

- lines spoken by one character to another, at moments when the events described are shown on screen rather than the act of telling about them;

- lines spoken by a character looking back at earlier events that are shown on screen but who is not seen in the act of telling about them;

- lines spoken by an unseen, anonymous narrator; or

- lines ostensibly spoken by the filmmaker, not visible in the act of speaking them.

Each of these varieties of voice-over will be illustrated by two examples. The images accompanying each example should be viewed as representative rather than indicative of the number of shots seen onscreen while the cited narration is heard.

1. Inner voice

The unspoken thoughts of a character in the fiction’s here and now, not addressed to any other character and generally heard only by the viewer who sees the character thinking the thoughts – though in exceptional cases, such as Wings of Desire, angels are able to hear these inner thoughts. In all such cases, frontal close-ups are essential for the viewer to see that the character’s lips are not moving.

Example 1: Wings of Desire / Der Himmel Über Berlin

Wim Wenders, West Germany/France, 1987.

The inner thoughts which we hear going through Peter Falk’s mind in these and other scenes, were recorded in a sound studio in Los Angeles, with Wenders directing over a long-distance telephone line, months after those scenes were shot. Wenders had sent Falk some pages to use for these voice-overs, but they just didn’t work. Instead of reading the prepared lines, Falk then said, “Let me close my eyes,” after which he invented the material that would eventually be used in the sound track of the film. Almost all of his inner monologues were improvised by Peter Falk, including the memorable lines spoken at the film shoot, as he sketches the woman wearing a yellow star, with the angel Damiel (played by Bruno Ganz) hearing all the inner thoughts:

Example 2: For Whom the Bell Tolls

Sam Wood, USA, 1943

In the final scene of this film about the Spanish civil war, the main character – Robert Jordan (Gary Cooper) – has been wounded and remains behind at a mountain pass with a machine gun to hold off the approaching fascists while his lover, Maria, and other members of his Republican group make their getaway. We hear his inner thoughts in these final moments of the film, based on the 1940 Hemingway novel with the same title.

2. Character addresses character

In a given shot or series of shots, one character addresses another or two characters may address one another, while what we see onscreen is a setting evoked by the spoken lines and in which the spoken lines would not be heard. The audio would naturally be recorded independently of the camerawork.

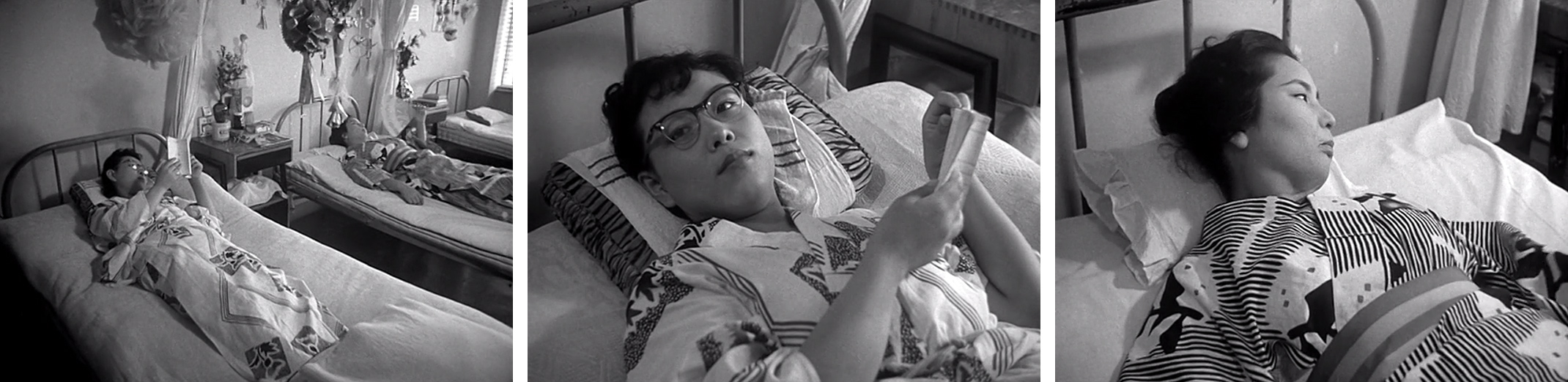

Example 1: Hiroshima Mon Amour

Alain Resnais, director; Marguerite Duras, scenario and dialogues; France, 1959

In this film’s opening sequence, we see the intertwined torsos of two lovers and hear in voice-over what they say to one another, while images of Hiroshima are shown onscreen. Music is heard throughout this sequence. The male character speaks French with a Japanese accent. My translations from the French.

Example 2: Rashomon

Akira Kurosawa, Japan, 1950.

In this first Japanese film to win international recognition, four different accounts are given of the same tragic event involving the rape or possible seduction of a bride and the death of her samurai husband. The viewer is left to consider which – if any – of the four accounts is the one to be trusted. The film operates in three time-frames: 1) the present in which a woodcutter, priest and commoner are taking shelter from the rain in the ruins of a city gate; 2) the giving of testimonies at court earlier that same day; and 3) the scene of the crime that had occurred three days earlier. Kozloff was right to point out that “contrary to common recollection” the film uses “only the barest snippets of voice-over” (62-63). There are for example no uses at all of the device in the wife’s testimony, and only one in the bandit Tajomaru’s (“I had never seen such fierceness in a woman.”) Voice-over is used a bit more in the woodcutter’s account, and mainly – though still relatively little – in the dead samurai’s testimony as channeled by a medium and primarily in this group of shots:

3. Character looking back

A character now situated at a later time than the events shown, looks back on those events. We never see narrators of this kind in the process of telling their stories. They speak only to us, not to any other character in the film. This distinguishes this form of voice-over from the previous one described, in which characters speak to one another in the film’s here-and-now.

Example 1: Laura

Otto Preminger, USA, 1944

Laura opens with a voice-over in which Waldo Lydecker (Clifton Web) – who will turn out to be the film’s culprit – looks back on an important moment in this murder mystery, positioning Laura (Gene Tierney), his own role and that of his clock and of the detective in the story (Dana Andrews).

Example 2: Sophie’s Choice

Alan J. Pakula. USA. 1982.

At the start of the film, before the first image of Stingo (Peter MacNicol) sitting in a bus is faded in, we begin to hear his voice-over. Whenever we see him on screen, it is in the past. We never see him in the present in the act of telling his story.

4. Anonymous unseen narrator

a) Framing the story, an impersonal voice not belonging to a character and in no way self-referential, sets the stage for the viewer at the film’s start. Frequently used in 20th century documentaries where it is sometimes called “the voice of God,” it was far less commonly used in fiction films.

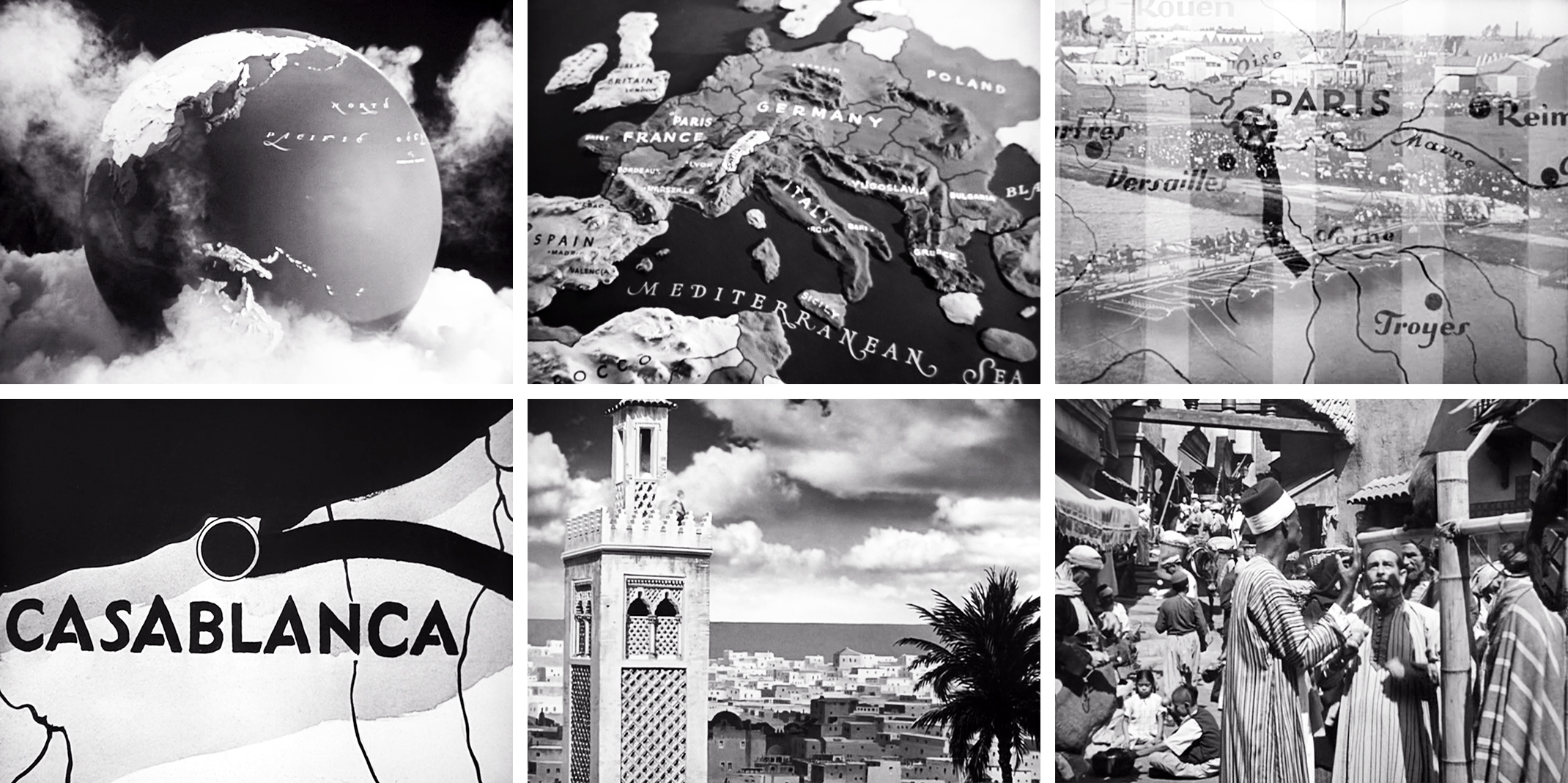

Example: Casablanca

Michael Curtiz, USA, 1942.

The opening voice-over in Casablanca is probably the best known example of an anonymous unseen narrator in feature film history.

b) Framing the story, an unidentified but more personal and self-referential voice sets the stage for the viewer at the film’s start.

Example 1: The Third Man

Carol Reed, UK, 1949.

As a British-American coproduction, with Alexander Korda in charge in the UK and David O. Selznik representing the Hollywood interests in the film, two versions of The Third Man were initially made, with the main difference lying in the voice-over that opens the film. In the UK version quoted below, the narration is spoken by director Carol Reed, but without presenting himself as filmmaker This is the only surviving version. In the defunct American version, it was Joseph Cotton who spoke the voice-over, ending with the words: Anyway, I was dead broke when I got to Vienna. A close pal of mine had wired me offering me a job doing publicity work for some kind of a charity he was running. I’m a writer, name’s Martins, Holly Martins. Anyway down I came all the way to old Vienna happy as a lark and without a dime.

This final version, spoken by an unidentified Carol Reed, fits in perfectly here as an anonymous yet self-referential voice, while the discarded Joseph Cotton version would have been listed as spoken by a character looking back and not visible in the act of speaking the voice-over.

Example 2: A Matter of Life and Death (aka Stairway to Heaven)

Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, UK, 1946.

Widely considered one of the greatest films ever made, A Matter of Life and Death (called Stairway to Heaven in the U.S.) was originally intended to improve Anglo-American relations. The film opens with a galactic perspective as we hear an anonymous voice first tell about the heavens and finally shift focus to the planet earth during the Second World War.

Images of two characters are then faded in – first Air Controller June (Kim Hunter) in her control tower, and then Squadron Leader Peter Carter (David Niven) in the cockpit of his burning Lancaster bomber. As their dialogue continues, we are treated to what may well be one of the most memorable scenes in film history.

5. Filmmaker’s voice

The narrative voice belongs at least implicitly to the filmmaker, for example in a trial-and-error process of writing the screenplay with Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue playing loudly in the background, as at the start of Manhattan where the narrator will turn out to be the main character, Isaac Davis (Woody Allen); or with the producer – who will never be seen – helping to introduce the film at the start of Naked City and to close it at the end.

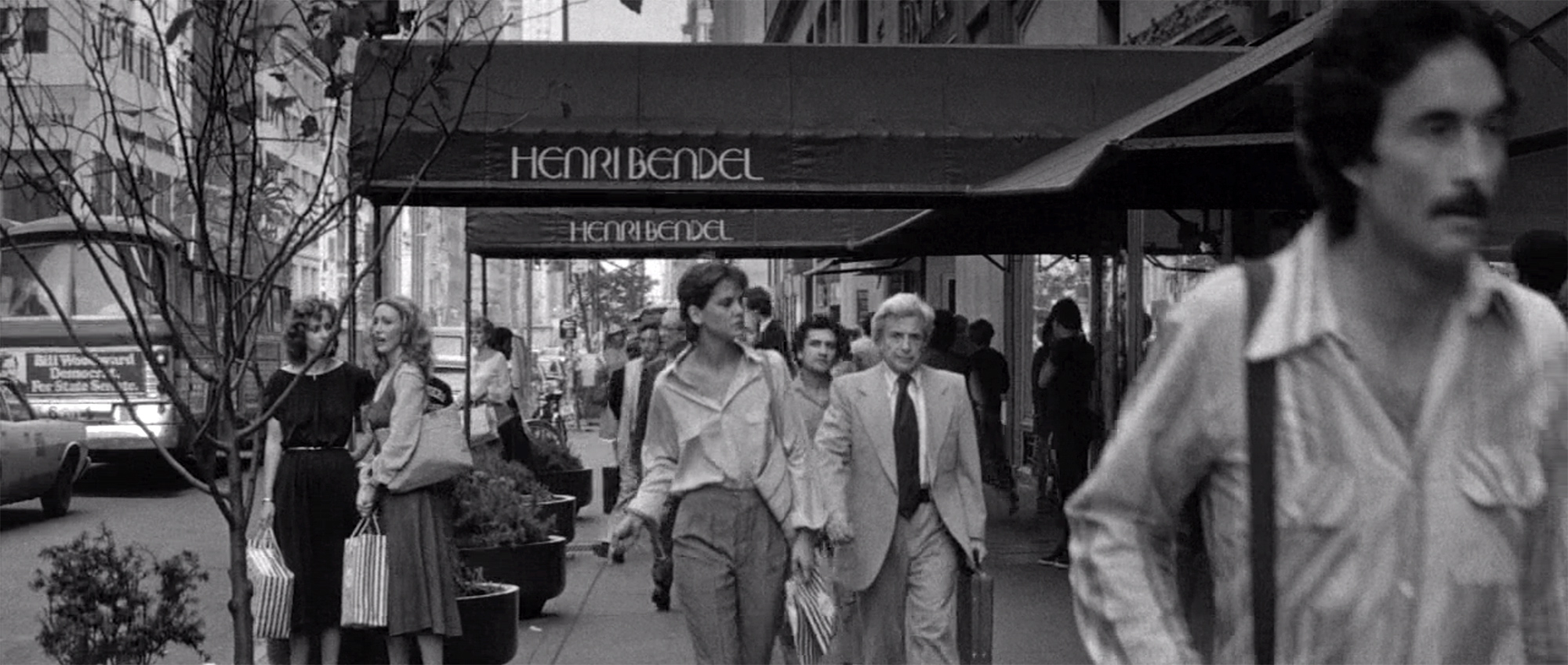

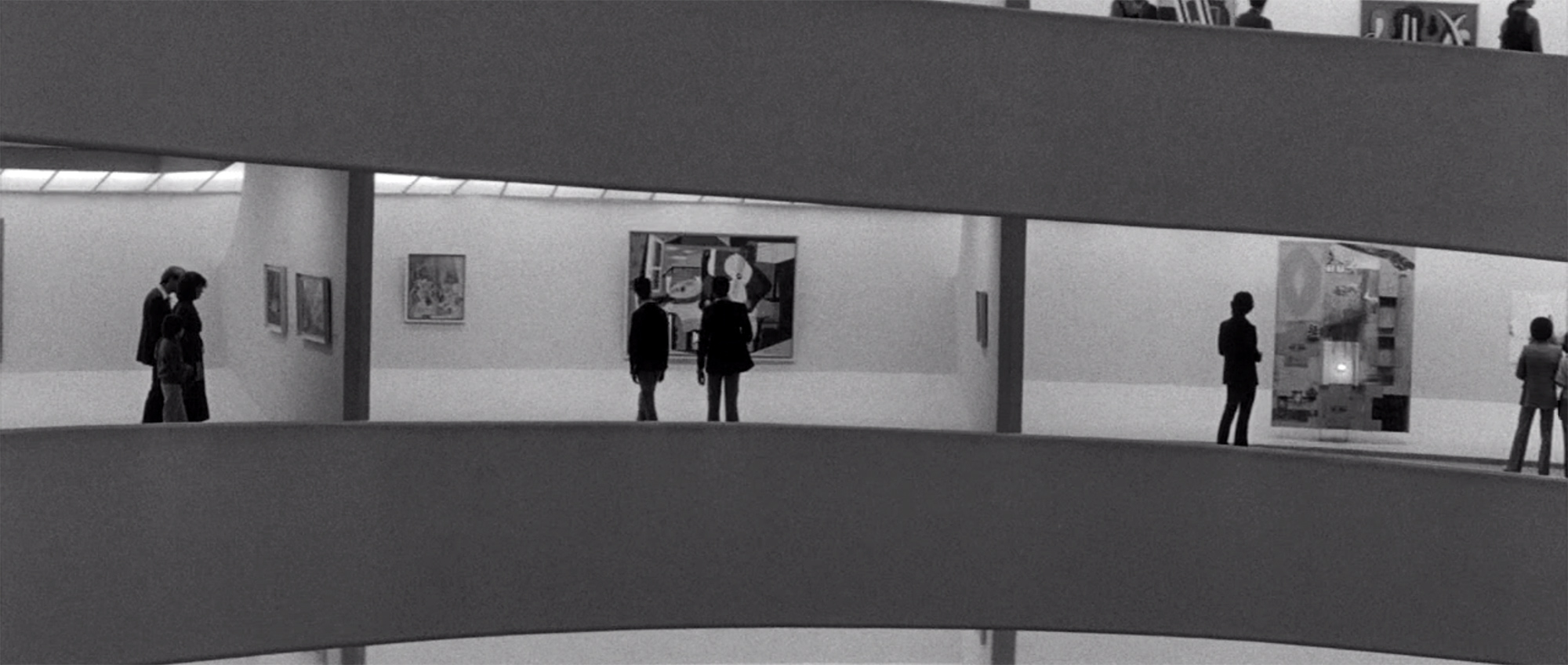

Example 1: Manhattan

Woody Allen, USA, 1979.

Example 2: The Naked City

Jules Dassin, USA, 1948

Overview of the five types of voice-over

- inner thoughts of a character heard while his or her lips are shown to be unmoving

– Wings of Desire

– For Whom the Bell Tolls - lines spoken by characters to each other, with the act of speaking not shown onscreen when the voices are heard

– Hiroshima Mon Amour

– Rashomon - lines spoken by a character looking back and not visible in the act of speaking

– Sophie’s Choice

– Laura - lines spoken by an unseen, anonymous narrator

a) Impersonal voice

– Casablanca

b) Personal voice

– The Third Man

– A Matter of Life and Death - lines ostensibly spoken by the filmmaker

a) in the process of developing the screenplay, with the narrator/screenwriter turning out to be the main character

– Manhattan

b) with the producer – never visible – opening and closing the film

– Naked City

Conclusion

A personal motivation for writing this article was to counteract a bias against voice-over by re-examining masterful uses of the device in films I love. Though beginners often resort to voice-over when they are unable to tell their stories cinematically, that doesn’t mean that there is anything wrong with the device itself when skillfully used by experienced storytellers. Perhaps the reader has also welcomed an opportunity to appreciate a narrative device that is often unfairly dismissed as uncinematic.

In the examples discussed above, we have seen how beautifully voice-over can be used to bring us into the mind of one character while illustrating the mind-reading abilities of another (Wings of Desire); or to give a main character the final word when there is no one there for him to address (For Whom the Bell Tolls); or to enable the viewer to see what characters describe (Hiroshima Mon Amour, Rashomon); or to position characters and sneak in backstory painlessly (Sophie’s Choice, Laura); or to establish a larger framework before bringing the main characters into play (Casablanca, The Third Man, A Matter of Life or Death); or to weave into the cinematic experience an acknowledgement that it is just that (Manhattan, Naked City).

The five types of voice-over described here may not be the only ones that have ever been used in feature films. But they are arguably the most important ones and well worth the closer look they have just been given.

Bibliography

- Aspen, Peter (2007). “A Matter of Life and Death”, Financial Times, 4 May 2007.

- Billson, Anne (2013). “Do voice-overs ruin films?” The Telegraph, 24 May, 2013.

- Chion, Michel (1999). The Voice in Cinema. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999.

- Genette, Gérard (1980). Narrative Discourse. An Essay in Method. New York: Cornell University Press.

- Kozloff, Sarah (1984). “Humanizing ’The Voice of God’: Narration in The Naked City.” Cinema Journal , Summer, Vol. 23, No. 4 (Summer), pp. 41-53.

- Kozloff, Sarah (1988). Invisible Storytellers. Voice-over Narration in American Fiction Film. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Raskin, Richard (1995). “What is Peter Falk doing in Wings of Desire?” Nordisk Film Forskning 1975-1995. En bibliografi & 10 essays in anledning af filmens 100 år, ed. Peder Grøngaard. Aarhus: Nordisk Dokumentationscentral for Massekommunikationsforskning, 1995, pp. 115-120.