Why do we rarely see him carry out the actual act of killing while we often get to see him eat a fancy dinner? Whenever the sadistic cannibal Hannibal Lecter enjoys another gourmet meal, this broadcast TV series displays culinary cannibalism with luxurious aesthetics that could rival most cooking shows. But why? The purpose of this article is to analyze the many appeals of NBC’s Hannibal and especially its food strategies.

Origin

The stories about Hannibal Lecter begin with Thomas Harris’ four books Red Dragon (1981), Silence of the Lambs (1988), Hannibal (1999) and Hannibal Rising (2006). This tetralogy has since been adapted and made into five different films: Manhunter (dir. Michael Mann, 1986), Silence of the Lambs (dir. Jonathan Demme, 1991), Hannibal (dir. Ridley Scott, 2001), Red Dragon (dir. Brett Ratner, 2002), and Hannibal Rising (dir. Peter Webber, 2007).

All the films have been produced by Dino and Martha De Laurentiis – except Silence of the Lambs which won five Academy Awards (Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor, Best Actress and Best Adapted Screenplay) and was arguably the most successful of the films. After the disappointing Manhunter Dino and Martha De Laurentiis still owned the film rights to the characters from Red Dragon including Hannibal Lecter. So when director Jonathan Demme approached the De Laurentiises to borrow the rights to the Hannibal character, they gave it away for free (Bernstein, 2001). This may have been a mistake at the time considering the earnings and success that Silence of the Lambs generated. But in the long run Hannibal Lecter has become a very popular, valuable, and long-running asset (also for these producers).

After a dormant period with no new adaptations of the Hannibal Lecter franchise, in 2013 the American broadcast network NBC decided to bet on Bryan Fuller to successfully reinterpret the Hannibal universe into a broadcast TV series. By being a part of this larger intertextual franchise a series like Hannibal can make large or small changes to the existing mythology, create anticipation and curiosity, assume a basic viewer awareness of the central characters, and provide hidden intertextual references and “Easter eggs” for dedicated fans of the books and film adaptations (Mittell 2015, p. 173). But by having the series start as a prequel taking place before the Red Dragon events, Fuller’s TV interpretation also allows itself to create new and previously unexplored stories.

Some central characters have also been added or changed, making the TV show stand out from the books: Dr. Bedelia Du Maurier (new), Dr. Alana Bloom (now a woman, was named Alan Bloom in the books), Miriam Lass (new, a trainee somewhat reminiscent of Clarice Starling, who could not be included in the TV series because of copyright issues), Freddie Lounds (now a woman, was a man in the books), and Dr. Abel Gideon (new). So we can deduce that four women and one man have been added to the menu (maybe to make the show’s gender balance more equal and modern).

Genre and style

In the following genre comparison, I will compare Hannibal (NBC, 2013-15) to similar American TV shows from the same period. At first glance the TV series Hannibal might look like a fairly harmless police procedural show. The first couple of shots of the pilot episode show iconic police procedural images like a house teeming with police officers, a pool of blood on the floor, two dead bodies, a body being put in a body bag (fig. 1), all of which suggests a home invasion. This sort of scene could point to an episodic police procedural like CSI: Crime Scene Investigation (CBS, 2000-15) or Bones (Fox, 2005-), a subgenre within detective fiction where most episodes start with the discovery of a new crime scene and focus on the forensic and police-related details of crime solving (Nichols-Pethick 2012, p. 155).

The following images show an investigator (the character Will Graham played by Hugh Dancy) observing the crime scene with dramatic music and flashing police lights in the background. As Will slowly closes his eyes, the color-grading becomes warmer, the sirens disappear, and the sound of a heartbeat follows. Three light flashes wipe over the screen – a setup mimicking a pendulum involved in Will’s personal therapy sessions later in season 1. These three pendulum lights become the signature of Will’s keen ability to reconstruct and reenact horrific crimes. This (almost superhuman) mental ability to solve crimes is reminiscent of crime/mystery protagonists like Patrick Jane from The Mentalist (CBS, 2008-15) but also classic puzzle-solving detectives like Sherlock Holmes.

A less conventional character trait follows as Will quite literally puts himself in the killer’s place and replays the horrific events in which he enters the house and shoots the couple living there while stating his catchphrase “This is my design” (1:58, 2:37). This mirror dialectic of crime fiction – where the detective has to mirror the killer in order to understand and solve the crime – has been a central appeal within the genre for a long time (Agger 2010, p. 171). Will’s ability to empathize and identify with the killer leads to him killing the real perpetrator, Garret Jacob Hobbs, in the end of the pilot episode. Thus, Will becomes an actual killer himself and he has a lot of mental anguish about this because he seemingly liked the act of killing. In this way, Will is somewhat like Dexter (Showtime, 2006-13): An anti-hero protagonist with a killer’s instinct who kills the real bad guys – thereby blurring the lines between good and evil.

Up to this point in this genre analysis of the pilot episode, Hannibal does not seem to be a particularly innovative show but rather similar to other police procedurals and crime dramas in American broadcast TV at the time (in 2013). And as the pilot episode progresses, the only clear-cut surprise is maybe that the presentation of the show’s title character Hannibal Lecter is delayed until about halfway through the episode (20:59). During the presentation of Hannibal’s character he is implicitly (and falsely) linked to the serial killings of eight different girls and the show’s images indicate that Hannibal ate their organs (a false trail when it was in fact Hobbs who did it). At this moment when Hannibal is introduced, the show’s aesthetics change (fig. 2): Low-key lighting, classical piano music, and upper-class vibes make him stand out compared to the bright procedural scenes from FBI headquarters in Quantico, Virginia (fig. 3). His plate of food looks like delicious haute cuisine (fig. 4) while the dark images suggest moral decadence. Hannibal is stylistically introduced as an aesthete, an aristocrat (of noble descent, his father was a count), and a gourmet (and gourmet magazine author). Even though he could be eating human flesh, the food looks paradoxically gorgeous. The images create a distinction between the police procedural genre and style on one side and Hannibal’s upper-class style on the other side – as if he may bring something unusual to this TV genre.

Narrative

After the short eating scene the next shot displays an extended hand, a man begging for mercy: “Please” (21:36). Combined with the presentation of a character which audiences might already remember from the books and movies as a famous serial killer, one might expect to see him kill someone. But instead Hannibal hands him a tissue as it is a therapy session with Hannibal as the psychiatrist. Again this TV show plays with potential genre expectations. The patient Franklyn is afraid of being eaten by an imaginary lion and Hannibal reassuringly says: “You have to convince yourself the lion is not in the room” (22:16). This is just one of many examples of narrative irony in this show and here it illustrates the ignorance of Franklyn and the FBI in the beginning of the series: Neither of them is aware of the hungry killer in the room. This psychiatrist appointed to help people is in fact a serial killer. And the knowledgeabilty (Bordwell 1985) of this circumstance is used to achieve narrative equality between Hannibal and the audience: Only the audience knows his secret. The possibility of his exposure and eventual capture creates the show’s primary narrative suspense where it uses retardation (ibid.) by repeatedly postponing this event: When will they discover that he is the killer and catch him?

Hannibal has some episodic narratives in its three 13-episode seasons, more precisely in season one in episodes 2, 4, 5, 8, 9 and 10, in season two in episodes 2, 4, 6, 8 and 9. And in season three the episodic structure is strikingly absent in favor of a more complex serial structure. By starting season one with half of the season dedicated to episodic narratives Hannibal’s narrative structure is seemingly not that complex. But as it turns out this might be a part of its strategy to play “the long game” and wait until the end of the second season before revealing how Lecter has been at least three steps ahead of Will, Jack Crawford, the other characters, and even the audience the entire time. The mix of episodic and serial narratives (and these long suppressed story arcs), hidden references, a second season that starts with an intense flash-forward to the season finale’s epic stand-off in Lecter’s kitchen, different types of gaps and hidden cues (fig. 5), and examples of lost time (experienced through the perspective of the protagonist Will) mimic a more complex narrative (Mittell 2006) which would normally be found in cable TV (HBO, Showtime, AMC, FX etc.). The “13 episodes per season” that Hannibal has is also sometimes referred to as “the cable model”. Therefore Hannibal initially lives up to certain genre expectations connected to broadcast network television but then goes above and beyond those expectations by mimicking cable television fiction.

Serial killing, cannibalism, and monsters

“The serial killer” as a character enjoys much attention these days in American TV and this character is particularly useful in TV fiction where the serialized nature of this type of fiction – and especially the episodic crime/mystery shows – requires an ongoing murder spree in order to sustain the narrative. But Lecter is both a serial killer and a cannibal. The ritual of humans eating humans, also called anthropophagy, has been one of humanity’s morbid fascinations for a long time. In order to specify the cannibalism in Hannibal it can be categorized as A) gastronomic cannibalism – killing someone for food and not because of starvation, honor, war or medicinal reasons – and as B) sadistic cannibalism where individuals are killed and eaten because of sadistic or psychopathological motives (Ullyatt 2012, p. 9).

Cannibalism is typically deemed uncivilized and often connected to primitive tribes living in some distant jungle far away from the white man. But in Hannibal Lecter’s case it is the white man himself – even a very sophisticated version of him – that has become cannibalistic. Maybe it is not accurate to call Lecter a “savage” because he is always in control and never careless. But he does display unruly behavior and loves to play games with the people around him. This is highlighted whenever he has dinner guests that are unknowingly eating human flesh (sometimes this is revealed to the audience and sometimes it’s only discretely suggested). Lecter as a character takes pleasure in the knowledge of tricking people into taking part of one of the modern world’s last taboos.

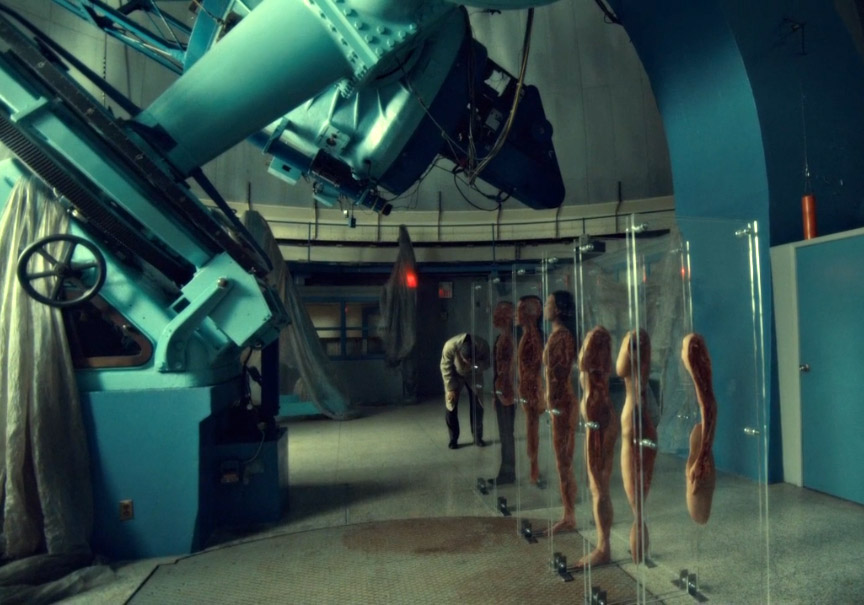

This unruly and yet controlled aspect of him is most apparent when his victims are found. Lecter is presented as an artistic serial killer that makes elaborate installations out of his victims, making them into works of art. An example of this occurs in season 2, episode 5, when a body is found sliced into sections and put on display (fig. 6). These sadistic serial killings done by Lecter and other “guest killers” provide a sprinkle of horror to the show’s genre mix. Hannibal could be called a melodrama because of the focus on emotional, tragic, violent, and intriguing relationships and a crime/mystery show because of the focus on puzzle solving and murder investigation (Cawelti 1976). But the element of horror is also present and in a quite gory manner with lots of blood, guts and horrific details. Cawelti’s version of horror called “alien beings or states” requires a monster and in Hannibal the monster is obviously the title character. But the protagonist Will is also at times awarded some of these monstrous qualities. Where Jack Crawford is the solid and sound policeman signifying normalcy and goodness, Hannibal and even Will often play with the boundaries between good and evil. The horror of Hannibal relies partly in the fact that the seemingly reliable psychiatrist turns out to be a manipulating psychopath and partly in the fear of the potential urges within Will. They each represent these two versions of the monster. And as the show progresses, it presents the possibility of Will succumbing to Hannibal’s influence resulting in the unification of the two (which is a different and maybe more progressive version of the story than in the books and films).

Making cannibalism look tasty – food strategies in Hannibal

To get to the core of the reinterpretation that this TV series presents, let us ask ourselves: What food-related strategies does Hannibal employ? I would argue that this TV show goes to great lengths to highlight the food-related aspects of the narrative and does this to a higher extent than the films do. This choice displays the paradoxes regarding Lecter and his exquisite and yet cannibalistic cooking.

A) Instead of only focusing on the horrific consequences of his eating ritual the show chooses to highlight his culinary knowledge, perfect surgical technique, flawless preparations, and beautifully arranged meals (fig. 7). These cooking and eating scenes have so far been repeated again and again in the TV series and they seem to offer many different appeals to the viewer. A common pattern that first occurs in season 1, episode 7 and is repeated thereafter is that Lecter first goes through his neat box of hand-written recipe cards and chooses a gourmet recipe. Next he goes through a rolodex with lots of business cards from rude people and he chooses a rude person to kill and devour. This is his preparation ritual where he procures meat while making the world a more polite place to live in.

The first time Lecter is introduced in the series, he is eating. But we rarely get to see him actually kill someone. Often the images just show him returning to the fridge with a vacuum-packed piece of meat and later we see him cooking it. And so the show deliberately chooses to accentuate the planning and cooking of this cannibalistic cuisine but not the murder (fig. 8).

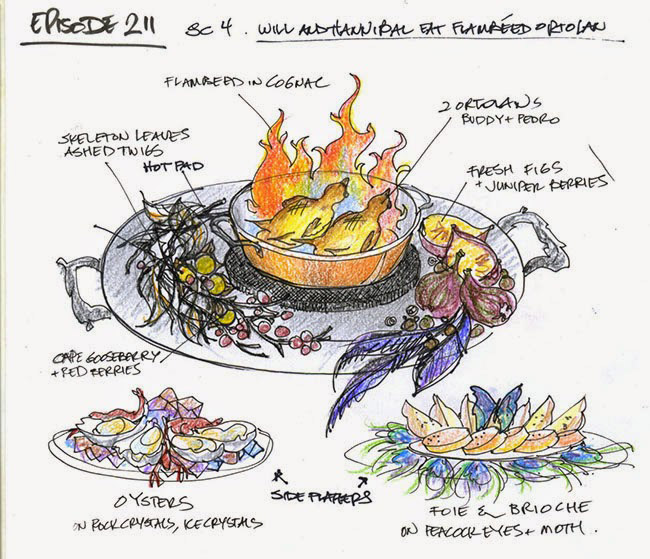

B) These elaborate dishes also owe much to the show’s food stylist Janice Poon who designs all the meals and food arrangements. Poon’s blog delivers many insights on food design from a technical perspective by showing her work process and many spectacular sketches like this one (fig. 9) Poon’s food-related production design is not only about making stuff look like human flesh (although this is a recurring subject throughout her blog) but a central part of the show’s efforts to make cannibalism look tasty (fig. 10). That the food design is this elaborate and central is a testament to the emphasis this series seems to put on food as an essential theme.

C) Another part of the food-related strategies has to do with the episode titles. In season 1, the titles are borrowed from the French culinary vocabulary (Apéritif etc.), season 2 uses the Japanese culinary vocabulary (Kaiseki meaning a certain multi-course culinary artform honoring taste and aesthetic etc.), and season 3 starts with an Italian culinary vocabulary (Antipasto etc.) but then goes on to use phrases related to William Blake’s Red Dragon-paintings for the last half of season 3. Besides the episode titles, food is even a central part of the dialogue where it is frequently used as a metaphorical language along with hunting and fishing analogies (fig. 11).

D) Furthermore, Lecter’s kitchen and dining room are central places in the show. It is here that he is first introduced and it is also the stage for the final confrontation in the season 2 finale. And the very last seconds of the season 3 finale take place around a well-decorated dinner table. So even in the choices of the locations for the most crucial scenes food appears to be somewhat highlighted.

E) And lastly, the show’s title sequence shows Lecter’s face created by a red liquid resembling blood or wine connecting food with mortality (fig. 12).

Conclusion

Hannibal as a case exemplifies how a theme like food can permeate many different aspects of a TV series. By highlighting food as a theme in many different ways this TV reinterpretation delivers an unexpected insight into Hannibal Lecter as a multi-faceted character. He is a psychiatrist, an aristocrat, a gourmet, an artist, an art historian, a musical sophisticate, and a harpsichord player. But he is also an unruly cannibalistic serial killer with a keen love for eating, decapitating, and disemboweling people – especially the rude. And this complex nature of his is obvious in the show’s cooking and eating scenes through the use of narrative irony. Hannibal uses food as a theme that combines two seemingly incompatible aspects: gourmet food and cannibalism. This is the first and clearest paradox. But by doing this, the show also displays an awareness of the “terrible beauty” (Turnbull 2007, p. 58 f.) of Hannibal Lecter and Thomas Harris’ stories about him. And this terrible beauty is the second and more subtle paradox. The choice of placing the show on an undecided and narrow line between the terrible and the beautiful where the decadent resides could be interpreted as an effort to stay true to the nature of the narrative. All of this makes Hannibal more similar to complex and progressive cable shows than the episodic police procedural that has dominated the American broadcast networks’ take on the crime genre. That the show was cancelled due to low ratings, could be the unfortunate fate of trying to innovate network television. Hannibal can also serve as an example of how food design can play a major role in production design in modern TV and fiction film. The impressive longevity of this complex character might be because of his many nuances and therefore we probably haven’t seen the last of Dr. Lecter yet.

Facts

Hannibal (NBC, 2013-15), created by Bryan Fuller, 3 seasons, 39 episodes.

Literature

- Agger, Gunhild (2010): ”Køn, krimi og melodrama – da kvinderne kom ind i tv-serierne”. In: Lausten, Pia S. & Toftgaard, Anders (ed.): En verden af krimier (pp. 167-183). Aarhus: Klim.

- Bernstein, Jill (2001): ”But Dino, I don’t want to make a film about elephants…”, The Guardian, February 9, 2001.

- Bordwell, David (1985): “Principles of Narration”. In: Narration in the Fiction Film (s. 48-62). London: Routledge.

- Cawelti, John (1976): Adventure, Mystery, and Romance. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Mittell, Jason (2006): ”Narrative Complexity in Contemporary American Television”. In: Velvet Light Trap, no. 58.

- Mittell, Jason (2015): Complex TV: The Poetics of Contemporary Television Storytelling. New York: New York University Press.

- Nichols-Pethick, Jonathan (2012): TV Cops: The Contemporary American Television Police Drama. London & New York: Routledge.

- Turnbull, Sue (2007): “The Best Serial Killer Novel: Red Dragon”. In: McKee, Alan (ed.): Beautiful things in popular culture. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

- Ullyatt, Tony (2012): “To Amuse the Mouth: Anthropophagy in Thomas Harris’s Tetralogy of Hannibal Lecter Novels”. In: Journal of Literary Studies, 28:1.