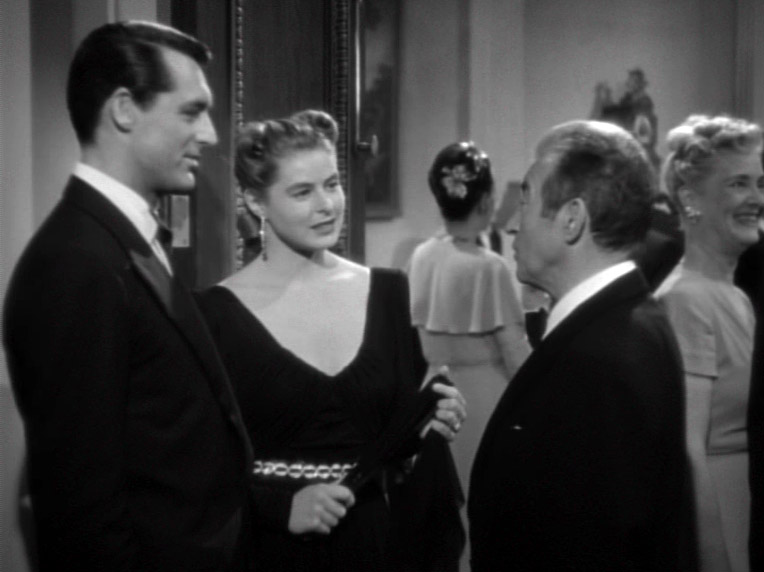

Notorious (1946) remains one of the most compelling and mysterious of Alfred Hitchcock’s films. As a three-hander tracing the shifting, dramatic relationships between a group of characters – Alicia (Ingrid Bergman), Devlin (Cary Grant) and Alex (Claude Rains) (Fig.1) – it has proved remarkably open to different responses and readings. It is particularly striking that while virtually all critics agree that Hitchcock’s central strategy is strategically to shift the narrational point of view (POV) throughout the film – favouring one character and then another, creating a mosaic of viewer identifications – almost none concurs with another on exactly where and how this happens, and which particular characters Hitchcock is favouring in any one scene. Notorious veritably demands that we explore our more free-floating, subtle responses to the behaviour of characters and their relationships. The question of point of view – how far the literal POV or more general standpoint of characters is aligned with the Hitchcock’s own attitude – is complex, and constantly unsettled by the film itself.

In fact, Notorious is an extraordinarily open film. It is this openness, especially in relation to the character triangle which is its main subject, that I wish to discuss here. What makes Notorious such a unique achievement is the way it actively creates and structures this openness on many levels simultaneously.

Generic Openness

To begin with, to what genre does it truly belong? The film exploits its hovering, intermediate status between several available genres. Two particular genres that Stanley Cavell has addressed feed a great deal into Notorious, especially via its chosen stars – the romantic “comedies of remarriage” (where Grant so often featured), and the tragic “melodramas of the unknown woman” (like Gaslight [1944] with Bergman) (Cavell 1981, Cavell 1996). For if Hitchcock’s film brilliantly extrapolates from the hints of a dark side in the Grant persona that were evident in earlier films like Penny Serenade (1941), it also locates Bergman inside a tale where she is (in Tania Modleski’s chapter title) “The Woman Who Was Known Too Much” (Modleski 1988).

Another reading of Notorious, centring on Devlin and his evolution, is also possible. A particular line from that final sequence is one of the most resonant of the entire film: “I was a fat headed guy full of pain … ”. Today, one can experience the film as a male melodrama, a terse but trembling male weepie. Here, it would join a tradition running from certain of Nicholas Ray’s postwar films (especially On Dangerous Ground [1952] and In a Lonely Place [1950]) to David Cronenberg’s contemporary horror psychodramas (Dead Ringers [1988], Spider [2002]) – movies that, beginning from an overwhelming sense of masculine guilt and self-loathing, confront the protagonist with his own inherently violent impulses, and force him somehow to work them out of his system so that he can finally rejoin the world of daily sociality and intimacy, or die unreconciled. Vertigo (1958), too, can be approached in this light (fig.2).

Like Modleski, Dana Polan describes the generic mix of the film in yet another way (Polan 1989, pp. 280-281). Both rightly stress that the emotional drama of the film as it pivots on Alicia evokes the genre of the Female Gothic – with its familiar themes of masochism, sickness, entrapment in a house, and the ambiguous threat offered by male saviours. This essentially female story is then counterposed dialogically to the masculine thriller adventures that are centred on Devlin and his frankly Oedipal struggle with Alex. The shuffling between, and comparison of, differently gendered parts of the film is crucial to its complex emotional effects.

One further generic description suggests itself. The film starts out something like a film noir, with its title and opening scenes evoking the perhaps dangerous enigma of Alicia’s sexuality and her political affiliations. These ambiguities are soon dispelled, to be replaced by others that centre on Devlin’s psychology, or even psychopathology – what does he really want, what does he really feel towards Alicia? – and the twisted, perhaps perverse logic of Alicia and Devlin’s relationship. In this respect, the film evokes a less well recognised, more subterranean, less moored genre of the ‘40s and ‘50s, the film blanc. This is an unstable term in film literature, sometimes used to denote romances between humans and ghosts/angels (Meet Joe Black [1998], Wings of Desire [1987]); or contemporary thrillers with snowy settings (Fargo [1995], Insomnia [2002]). I am using it to describe a genre – which includes Otto Preminger’s Angel Face (1953) and Whirlpool (1949), Jacques Tourneur’s supernatural fantasies made with Val Lewton, Edgar G. Ulmer’s Ruthless (1948), some of Jean Renoir’s and Fritz Lang’s American films – in which nocturnal and nightmarish elements are displaced by the diurnal and quotidian; the thriller elements of the plot become attenuated, almost irrelevant; and the mystery explored is invariably the mystery of personal motivations and relationships (on film blanc as a supernatural genre see Roloff & Seeßleen 1980 – for a usage closer to mine see Johnson 1997, pp. 70-73).

All these films blancs have an atmosphere of the uncanny – not the dark underworld, but the naggingly unsettled and unsettling everyday, the well-lit space of a home which is in fact distressingly unhomely. As critic-screenwriter Pascal Bonitzer has argued, this sense of the uncanny is a key defining feature of Hitchcock’s storytelling sensibility. “The unheimlich, or the uncanny, occurs when a known object suddenly presents an unfamiliar aspect. It is the same, yet it is other” (Bonitzer 1992, p. 153).

Mixed Emotions

Another aspect of the film’s openness is the space it explores between the type that a character fills – with a more or less determined generic role – and the intricacies of his or her psychology, which allow for an excess and a freedom beyond strict ideological determinism. Consider the role of Alex in this regard, which presents us with a striking paradox. How do we square his obvious generic position in the scenario (as a cloying, slightly creepy, un-American Nazi) with the sense of pathos that François Truffaut shares with the director in their famous interview sessions: “It’s rather touching: the small man in love with a taller woman … ” (Truffaut 1986, p. 248).

As a type, Alex has a clear cinematic, generic pedigree. He is the older, smaller, foreign, sometimes politically reprehensible, possibly sexually perverse point of a classic Hollywood triangle (Fig.3). There are many personal and/or political fables that position one woman between such a man and another, more conventionally heroic one, taking her through to an ultimate moment of choice. Notorious and Morocco (1930), with Marlene Dietrich positioned between Adolphe Menjou and Gary Cooper, mark two key points in this history; others include Gilda (1946), Flame of Barbary Coast (1945), Casablanca (1942) and Deception (1946) – the last two featuring Claude Rains. The strict Oedipal logic of many plots of this type is clear, as Martha Wolfenstein and Nathan Constantin Leites in their 1950 book Movies: A Psychological Study first suggested: a young man who wins a woman and achieves power and authority by vanquishing the weak father who is his sexual rival (Wolfenstein & Leites 1950). In Notorious, Alex’s aberrant masculinity is given a crowning twist: not only is he small, Nazi and cultivated, he is also castrated by a monstrous, overbearing mother (played unforgettably by Leopoldine Konstantin).

Yet no viewer who is at all open to the emotional atmosphere of the film can remain satisfied for long with this analysis. The character of Alex seems to bear an emotion, and a meaning, in excess of this strict, determined, social-ideological role. The uniqueness of Notorious in this respect became startlingly clear when compared to Frank Borzage’s Strange Cargo (1940). Here, Peter Lorre takes the Alex role in a triangle with Joan Crawford and Clark Gable. In the crowning moment, when Crawford finally deserts Lorre for Gable, we get a final reaction shot of Lorre which is so brief, so insignificant and so forcibly drained of any possibility of identificatory emotion (sympathy, pity, tragedy) that it may as well not be there. The situation, with its moment of choice, is itself a typical one for films within this formula. The mixed emotions inherent in such a scenario run particularly high at the end of Notorious.

Here, our identification seems almost split three ways between Alex, Alicia and Devlin. Polan’s remark is pertinent: “In its variations on a theme, Notorious can suggest the permutational openness of the Gothic as symbolic form.” Polan refers to a feature of the film remarked on by many commentators: the spectre of interchangeability between Alex and Devlin, the reversal of their typed good and evil positions, especially in their acts of spying and aggression directed at Alicia. There is a system of suggestive rhymes across the length of the film: Alex’s poison is prefigured by Devlin’s looming, upside down glass of milk (Fig.4); Devlin’s punch is a preview of the brutal containment of Alicia carried out later. In relation to the typical wife-in-peril scenario of the female gothic (as in Gaslight), Polan stresses the boldness of the film in daring to suggest that “any man – husband or not, Nazi or figure of benign authority – can be a source of dread” (Polan 1986, p. 280).

Triangles

The permutational openness of Notorious has much to do with the fact that it is a classic three-hander drama. The potentially very rich and flexible structures of triangular stories in cinema have yet to be fully explored. With three key points in an interpersonal, intersubjective relation, there is always the possibility of suddenly shifting the narrational point of view in a new and surprising way, by taking a hitherto concealed angle on events. Post-Hitchcock filmmakers like Brian De Palma have often exploited this effect of shifting, sometimes to the point of sheer narrative vertigo (as in Dressed To Kill, 1980). A less pyrotechnical example – and thus one closer to the spirit and method of Notorious – is Carl Colpaert’s three-handed thriller Delusion (1990), a film that belongs to a modern tradition that grows out of the films blanc of the ‘40s and ‘50s, including Stephen Frears’ The Hit (1984), Eric Red’s Cohen and Tate (1989), and virtually all of Monte Hellman’s movies.

Hitchcock exploits a simple but brilliant structural device in Notorious – whom, out of the three characters, he chooses to end a scene on. Whenever a film does this – merely by closing a scene on a shot of a character reflecting, absorbing what has come before – it has the effect (ideally) of bringing us closer, for a moment, to that character’s subjectivity (Fig.5). Hitchcock rotates this scenographic grace note around all the points of his triangle. Each time it engenders a subtle emotional effect: shots of Devlin alone imply that he is less brutish than his actions towards Alicia have just made out; shots of Alicia draw us closer to her feelings of hurt, and her dilemma in being constantly unacknowledged by Devlin; shots of Alex allow him the kind of pathos denied to the typically evil, little foreigner.

On top of these shifts around and between the three central characters, Hitchcock superimposes another kind of narrational break – sudden leaps to events occurring outside the space of the triangle, but events which will have a determining effect on its shape, direction and outcome. In Hitchcock, as in Lang or De Palma, these kinds of overarching narrative intrusions often deal with powerful schemers on either side of the law – cops, espionage chiefs, underworld bosses, Dr Mabuse-type madmen in their surveillance centers – who are like chess masters moving character-pieces on the board of the narrative. In Notorious, the moments that take us to spy chief Prescott (Louis Calhern) function like this.

To Bonitzer and several contemporary commentators, Hitchcock’s triangles are essentially perverse configurations – structures where desire slips, treacherously, between one couple and another as they form, break apart and re-form within the space of the story. Within a perverse relationship, desire “never goes straight, one way”, as is said in Paul Morrissey’s Beethoven’s Nephew (1987) – it goes via detours, masks, calculated exchanges. In Lacanian psychoanalysis, desire’s perverse detour is particularly pronounced. A relationship between two people is always constituted in reference to a third, imaginary or absent person – and Hitchcock himself conceived even the most intimate moment between Bergman and Grant in Notorious as one that crucially included the audience, via his camera, in “a kind of temporary ménage à trois” (Truffaut 1986, p. 400).

In a perverse triangle, the excluded third point can be placed in many positions – foolish dupe, pathetic victim, sinister ringmaster, aggrieved lover, vengeful schemer – and can experience many possible emotions, from murderous envy to voyeuristic delight. Looking back from a contemporary vantage point at the film blanc, one sees such constitutive perversity in a heightened way, as if a hidden, secret aspect of these films had been suddenly, shockingly illuminated. Look at Lang’s Scarlet Street (1945) – with its relentlessly cruel diagram of perverse relations structured on narrative delusions, gaps in the characters’ knowledge and their differences of perspective – or Tourneur’s I Walked with a Zombie (1943). One reason this perversity is so apparent today is because of the efforts of those contemporary filmmakers who have rigorously applied themselves to the task of mutating Hitchcockian elements into their own style and vision – including Roman Polanski (Repulsion, 1965), Pedro Almodóvar (Matador, 1986), Valeria Sarmiento (Notre mariage, 1984), Bigas Luna (Anguish, 1987) and André Téchiné (Hôtel des Amériques, 1981). Such films have stressed, even celebrated perversity as part and parcel of a modern sensibility.

Perversity also invades the micro-structures of Hitchcock’s style – especially his famous, fetishistic way of framing and presenting bodily parts. Visual fetishism is a special kind of perverse detour, in which the camera, as it were, overinvests its gaze in a minor or insignificant detail at the momentary expense of the otherwise classical sense and direction of a scene. This is one of the structures that most clearly unites Hitchcock with Luis Buñuel, whose Surrealist method from Un chien andalou (1929) to That Obscure Object of Desire (1977) is largely based on the casual but deadly disruption of conventional scenes by fetishistic deviations and apparitions.

Thematic Openness

Here is an easily posed but surprisingly difficult question to answer: what is the theme of Notorious? The concept of a theme, so beloved of literary criticism, is best understood in its most supple and open sense, as a question or proposition which a work poses and explores. Hitchcock is a problem for thematic criticism. It seems fruitful enough to discuss some of his films starting from a broad thematic proposition – Vertigo is about the nature of romantic love, Shadow of a Doubt (1943) explores hidden aspects of the American family, Marnie (1964) is about repressed sexual trauma – but others, including The Birds (1963) (Fig.6) and Family Plot (1976), obstinately resist this kind of approach.

Criticism is often too ready to translate the specific materials of a film – the actuality of its characters, events, moods, textures – into a higher order of abstraction which is implicitly preferred because it is symbolic and general. But do filmmakers actually approach what they do in such an abstracted fashion? It is telling that, in a Cahiers du cinéma discussion among contemporary French directors (inclding Olivier Assayas and Jean-Claude Brisseau), there is much speculation on the subject of whichever film comes up, but never a dissertation on its theme. To André Téchiné’s remark that Robert Bresson’s films concern themselves with “the passage from ecstasy to love”, Benoît Jacquot responds: “That is a beautiful way of defining the subject of Pickpocket” (Round-table discussion 1989, p. 32).

This is not a merely semantic distinction: a subject is physical, contingent, material, specific, in a way that a theme may not be. So, what is the subject of Notorious? Beginning from Victor Perkins’ description of the embrace between Alicia and Alex in the bedroom antechamber – “we are shown (and shown that we are shown) the formality, the passion, the convincing enactment of impulse, and the calculation” (Perkins 1990, p. 61) – one might define the film’s subject as the mapping of particular, interrelated subjective and intersubjective states: emotional masquerade, suspicion, betrayal, desire, the passage from perverse to direct and authentic expression of love … In this light, I take the subject of the film to be that “fundamentally vulgar figure” itself, as it is called in Andrzej Zulawski’s Possession (1981): the character triangle, with every narrative and formal game, every perverse and humanist reflection, that it allows. Hitchcock’s play with this subject cannot be reduced to a moral statement or conclusion; more precisely, his film circles its three central characters and the enigmatic logic of their relationships. Indeed, the elusive aura of mystery crucial to the film blanc shrouds the subject as much as the characters. Watching Notorious, we circle the very mystery of its theme, or in Bonitzer’s formulation its “crucial secret, which contains all the ambiguities and things unspoken that constitute the fiction” (Bonitzer 1986, p. 38).

There is a tendency in much Hitchcock criticism to reduce the films to their set pieces and striking moments: shower scene, rock face chase, bird attack, dream sequence, etc. Stylistically, this approach – however poetic its appeal to the ‘special moments’ in the films, as in Godard’s presentation of the Master in Histoire(s) du cinéma – confines Hitchcock’s touch to broad effects of montage, bravura camera movements, and expressionist compositions. Approaching Notorious, this awestruck eye for spectacle pauses over not much of the film: the famous camera movement from the ceiling to the key in Alicia’s hand (Fig.7-8); the long take kissing scene; the final showdown on the stairs; the shot of Alicia imprisoned between Alex and his mother; the movement out from behind Grant’s dark head … but little else.

The Mise en Scène of Notorious

What is overwhelmingly absent from accounts that fixate on these high points is any holistic sense of the film’s mise en scène – and any apprehension that Notorious is, essentially, a film comprising scenes of characters talking to each other. Indeed, in this light, it needs to be appreciated as a chamber drama in the manner of In a Lonely Place, or indeed many of the films blancs. Notorious is a truly masterful chamber piece.

On this point, a comparison with the dismal television remake of Notorious (Colin Bucksey, 1992) is highly illuminating. Much could be said about this sorry attempt to modernise the script and its characters, but what is particularly striking is the complete absence of any intersubjective tension, any trembling aura of mystery, any uncanny strangeness in its bland mise en scène. This occurs in part because the ground rules of verisimilitude, of dramaturgical realism, have changed so radically between the classical Hollywood of 1946 and the television in-house styles of 1992. Revisiting the original after viewing the remake, one realises with a jolt how extraordinarily elliptical and abstract Hitchcock’s film is, how astonishingly minimal many of its scenes are. Its exchanges between pairs of characters are intensely focused, often hushed, with the least possible amount of extraneous, realistic detail; scenes begin rapidly, without undue exposition, as if to permutate the pairings.

Like other films blancs of the period, Notorious is a remarkably economic movie – tightly articulated to the point of a certain, dreamlike abstraction. Decades later it is this same, dreamlike permutation of a group of shadowy characters on the logic of what Bonitzer elsewhere calls a “strong, disquieting intersubjectivity” that modernist directors like Téchiné, Jacquot and Chantal Akerman will aspire to re-create and enhance (Bonitzer 1986, p. 39). “Today,” Bonitzer writes in his text on Notorious, “we are impressed by the power and efficacy of the scenario, and by the mounting intensity bestowed upon it by the staging” (Bonitzer 1992, p. 152). I would go further to suggest that Hecht’s script and Hitchcock’s mise en scène were conceived and mapped out in an absolutely interdependent relation.

The mise en scène of Notorious is based on a highly supple and varied but extremely systematic principle. The staging of the film, considered as a series of dialogue exchanges between couples, is devoted to the edgy impossibility of full, face-to-face intimacy. The variations on this face-off are amazingly inventive. Hitchcock explores just about every possible way that characters can be manœuvred into a dissymmetrical pictorial relation, constantly contriving imbalances in height, position, shape of gesture, direction of movement. This tension invades even the most normally stable of classical filmic figures, the shot-reverse shot volley – in the early party scene, Hitchcock has Bergman in close-up constantly tip so that half her face is obliterated by Grant’s shoulder (Fig.9).

Clearly, the systematic disequilibrium of Hitchcock’s mise en scène bears a close relation to the prevailing film blanc atmosphere of the uncanny. Bonitzer notes that, in so far as Hitchcock’s films are regularly and almost routinely devoted to the formation of a romantic couple, they develop a particularly fraught and unsettled picture of that couple, right to the very end of the story: many are the instances in the director’s work where characters bound in love and hate are pitching to and fro, grasping or struggling for balance, such as in The 39 Steps (1935) or the kissing scenes in Notorious and North by Northwest (1959) (Bonitzer 1992). And it is indeed telling that, at the centre of the mise en scène system of Notorious, even when Alicia and Devlin are finally locked in face to face embrace in the course of a dazzling sequence shot, Hitchcock introduces every conceivable note of tension, disruption and disequilibrium into an apparently harmonious and resolved continuity.

Social Mise en Scène

This tension also informs the very particular relation between characters and the camera raised earlier. One can sense that Hitchcock’s camera sometimes takes the position of a cold, unblinking, public eye – the social superego spying, recording, making implacably public the private lives and exchanges of its citizens. The figures in Notorious give off an air of always and unconsciously performing circumspectly for this social eye; that is one reason why they are turned toward the world rather than toward each other. A number of Hitchcock’s films offer, in this regard, a notion of mise en scène quite similar to the one theorised by Jean-Louis Comolli in 1980, which I would today call a social mise en scène (Martin 2014): a mapping of the changing postures and gestures that unfold “everywhere where the social regulations order the place, the behaviour and almost the ‘form’ of subjects in the various configurations in which they are caught” (Comolli 1980, p. 139). The constant, deforming pressure on private life by the public sphere – whether defined by family, social rituals or communal events – is a true Hitchcock obsession; works including the second version of The Man Who Knew Too Much (1955) and especially Shadow of a Doubt and are entirely built upon such a logic.

If we see the events and exchanges of Notorious as taking place in a social realm which is always too public for private intimacy ever properly to begin, the cleverness of Hitchcock’s work with Hecht becomes particularly apparent. So many of the scripted scenes are located in spaces where a certain propriety rules, even when emotions are simmering – restaurant, bar, racetrack, cab, plane. This propriety is doubled by the masquerades that go on, and contradicted by the emotions that rise up. In these spaces, Hitchcock is able to play in his staging on both the closeness of bodies and their postural stand-off, on both the stiffness of the characters and their palpable relief (or frustration) at not having to look directly at each other.

In an even more intricate way, Hitchcock is able to introduce into this behavioural dynamic tiny but dramatic flashes of a suspense effect linking up to the more heightened and action-oriented passages of the narrative: moments where one character suddenly sees and experiences what the other character does not, as in the plane scene where Devlin turns forward (after looking out the window) suddenly to find that Alicia has pushed herself across virtually right into his lap. He sees her and we enter into his awareness of her erotic presence, but she does not see or feel what he and we are seeing and feeling (Fig.10). (Again, the almost identically scripted scene in the remake loses virtually all the mise en scène dynamic, and thus the entire point, of this exchange.)

The Director of the Couple

Let us take a specific passage from the film, one that will serve to flesh out Godard’s suggestive assertion, made in 1957: “Hitchcock, we must not forget, is more than anyone else the director of the couple” (Milne 1972, p. 53). The kissing scene between Alicia and Devlin, just under twenty-three minutes into Notorious, is justly one of the most famous anthology moments in any Hitchcock film. But when put into the context of the whole work, what stands out is the interrelationship between both scenes in Alicia’s apartment: the sensual prelude to their romantic dinner, and then the awful actuality of it, once love has gone wrong and the lovers are set at absolute cross purposes.

One mark of an inventive filmmaker is how she or he is able to make deliberate, expressive, poetic use of the simplest, most predictable, everyday activities: eating a meal, washing the dishes, going for a drive, walking. Hitchcock uses all of these everyday actions in a very deliberate manner in Notorious. Equally, he explores the meanings of familiar architectural and domestic spaces. Observe, for instance, what the film does with the balcony in these apartment scenes. At first the balcony provides a view for that back-projected picture-postcard of exotic romance; then it virtually disappears, dissolves, as we draw towards, become absorbed in the lovers. It is, in other words, a space for intimacy, a private space. Later, the balcony is cold and dark and airy (Fig.11); it mirrors only the distances and mismatches between the characters as they bicker. Suddenly Alicia and Devlin are again stiff, posey, their movements unsure and interrupted; now the balcony is like just any other public space they inhabit, like a racetrack or a party or an airplane; it imposes the weight of the world on them. Hitchcock’s use of the balcony is only the first of so many telling and affecting transformations and differences that he works into this sequence.

The first scene in Alicia’s apartment is the perfect, blissful moment of love. Everything in it, on the level of staging, lighting, cutting and framing, creates that sense and sensation of perfect union, of the oneness of the lovers. In the first scene, there are only three shots. In the first two shots, we pass simply from the inside of the apartment to the balcony. The third shot is virtuosic; it runs for two minutes and forty seconds in a sinuous, unbroken movement. Alicia and Devlin talk and kiss, nibbling away over and over, their words always meaning and suggesting more than they are actually, literally, saying.

At the start of this grand shot, the camera moves in to abstract them from the world all around and in the background; then it follows the twosome right in close, keeping both their heads in view the whole time. Outside and inside the apartment are joined, unfolding in one continuous strip of space, bound by an unwavering, sensual luminosity. When a telephone is used in the course of this shot, Hitchcock doesn’t dip his camera to show us something so banal; we can hear it, we know it is there, but we just want to keep looking at these two in the same way that they are looking at each other. Hitchcock often said that he wanted his camera to behave like a third character in a scene, insinuated into its very fabric; the camera allows us to become an invisible, all-seeing third party in this gorgeous arabesque.

How different it all is an hour later (in plot time), when Devlin returns without his bottle of champagne. That bottle is the clever thread that links and ties up everything: he is sent off to buy it; then he has it, but he inadvertently leaves it behind, in a huff; finally he wonders, distractedly, where he misplaced it – and thus the scene ends on this melancholic note of irresolution, this sign of denial in motion. Where all was oneness and fluidity, now everything, under a sky that has grown suddenly, ominously black, is chopped up, separated, disconnected, fragmented in every way possible.

Instead of just three shots, now there are thirty-two. A cruel dance occurs: every time the two get near each other, one instantly moves away. And they are never even on the same level anymore, height-wise: she sits, he stands, they keep creating all kinds of dissymmetries between them. That poignant image of Alicia taking a drink behind the curtained window clinches (Fig.12) the barrier between them, marking the beginning of mutual secrets and misunderstandings.

Hitchcock has here found a way to make expressive use of one of the most basic elements of Hollywood grammar: the movement from a two-shot (two people in the frame together at the same time) to a volley of ‘singles’, a shot of only him or her. In the first apartment scene, there are no singles. When Hitchcock finally introduces them, as things are going bad, they bespeak solitude, distance, the incommensurable planets of this man and woman. There is a truly palpable edit in the scene – physically felt by the viewer like a slap in the face – when Hitchcock goes from the two-shot of Alicia and Devlin to just Alicia in close-up as she says the loaded line: “Right below the belt, every time”.

Circles

This essay has presented a fragmentary discussion of Notorious. I have not wanted to work towards a systematic textual analysis – one that scans the film and tries to cohere it in the unfolding of its articulations. On the contrary, I have endeavoured to circle the film (in itself, and in relation to those that influenced it, and those it has influenced) – just as, I believe, the film circles its characters, situations, themes. I have also offered a morsel of scene analysis – so as to alternate a general view around the film (its genre, historical context) with some specific discussion about it (theme), and sometimes even inside it (style, mise en scène). What is important is to capture what Raymond Bellour once called the “textual volume” of a film, that “space that constitutes [the film’s elements] and is constituted by them” (Bellour 2000, p. 197). This is because, in its multiple resonances and various actual and virtual levels, film is “an art of suggestion, of rhetoric, of graphic-semantic construction”, as Raymond Durgnat has mused, with “nine tenths of it existing below the surface of the film, deep down in the spectator’s own mind” (Durgnat 1981, p. 10).

This state of film’s being poses a challenge to the act of critical writing. The attempt to respect and prolong – as well as critically discuss – a certain trembling, fragile, emotional quality unique to the film viewing experience is a task that many critics have pursued. Clearly, such a mission demands a style of critical writing which is close to a certain species of poetic literature – “critical poetry”, as Jean Cocteau once provocatively called it. Camille Paglia speaks of criticism as “ceremonial revivification”: “I try not to allude to but to re-create, to reproduce the first, baffling experience of reading a text or seeing a painting or film”. She quotes an aphorism coined by Harold Bloom: “The meaning of a poem can only be another poem” (Paglia 1992, p. 117).

Jean-Luc Godard once circled a similar truth when he remarked: “What is alive is not what’s on the screen, but what is between you and the screen.” Few films demonstrate this relation more profoundly, or command our poetic attention more fiercely, than Alfred Hitchcock’s Notorious.

Facts

Literature

- Bellour, Raymond. The Analysis of Film. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2000.

- Bonitzer, Pascal. “Une certaine tendance du cinéma américain”. Cahiers du cinéma, no. 382. April 1986.

- Bonitzer, Pascal. “Notorious”, in Slavoj Zizek (ed.), Everything You Always Wanted to Know about Lacan (But Were Afraid to Ask Hitchcock). London: Verso, 1992.

- Cavell, Stanley. Pursuits of Happiness: The Hollywood Comedy of Remarriage. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1981.

- Cavell, Stanley. Contesting Tears: The Hollywood Melodrama of the Unknown Woman. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1996.

- Comolli, Jean-Louis. “Machines of the Visible”, in Teresa de Lauretis & Stephen Heath (eds.), The Cinematic Apparatus. London: MacMillan, 1980.

- Durgnat, Raymond. “Towards Practical Criticism”. AFI Education Newsletter, Vol 4 No 4. March-April 1981.

- Johnson, William. “Enigma Variations”. Film Comment. November-December 1997.

- Martin, Adrian. Mise en scène and Film Style. London: Palgrave, 2014 (forthcoming).

- Milne, Tom (ed.). Godard on Godard. London: Secker & Warburg, 1972.

- Modleski, Tania. The Women Who Knew Too Much: Hitchcock and Feminist Theory. New York: Methuen, 1988.

- Paglia, Camille. Sex, Art, and American Culture. London: Viking, 1992.

- Perkins, V. F. “Film Authorship: The Premature Burial”. Cineaction!, no. 21/22. Summer/Fall 1990.

- Polan, Dana. Power and Paranoia: History, Narrative, and The American Cinema, 1940-1950. New York: Columbia University Press, 1986.

- Roloff, Bernhard & Georg Seeßleen (eds.). Kino des Utopischen. Geschichte und Mythologie des Science Fiction Films. Hamburg: Rowohlt, 1980.

- Round-table discussion. “Autour de Pickpocket”, Cahiers du cinéma, no. 416. February 1989.

- Truffaut, François. Hitchcock. London: Paladin, 1986.

- Wolfenstein, Martha & Nathan Constantin Leites. Movies: A Psychological Study. Chicago: Free Press, 1950.